Japanese Breakfast’s awaited return pens character studies of destructive impulsivity in lush, gothic terms for an intensely rewarding tableau of macho-pessimism.

Michelle Zauner, frontwoman of indie-pop unit Japanese Breakfast, had a wild 2021. Japanese Breakfast’s bright, convivial album, Jubilee, charted on the Billboard 200 and earned her a Grammy nomination for Best Alternative Album and Best New Artist. Meanwhile, her memoir, Crying in H Mart, which was released just two months earlier, topped The New York Times bestseller list and remained there for a year.

Zauner, who had recently emerged in Oregon’s DIY punk scene, said yes to every interview and every show until she found herself playing six shows a week for six weeks straight. You’ve seen this film before: her mental and physical health deteriorated into fits of stage fright, persistent stomachaches, and guilty melancholia. So once the twofer Jubilee and Crying in H Mart circuit wound down, she told her band she was taking a year off. She wrote a new, darker record, bloodletting the thorny feelings Jubilee couldn’t accommodate, then spent a year in South Korea studying Korean and writing her next novel.

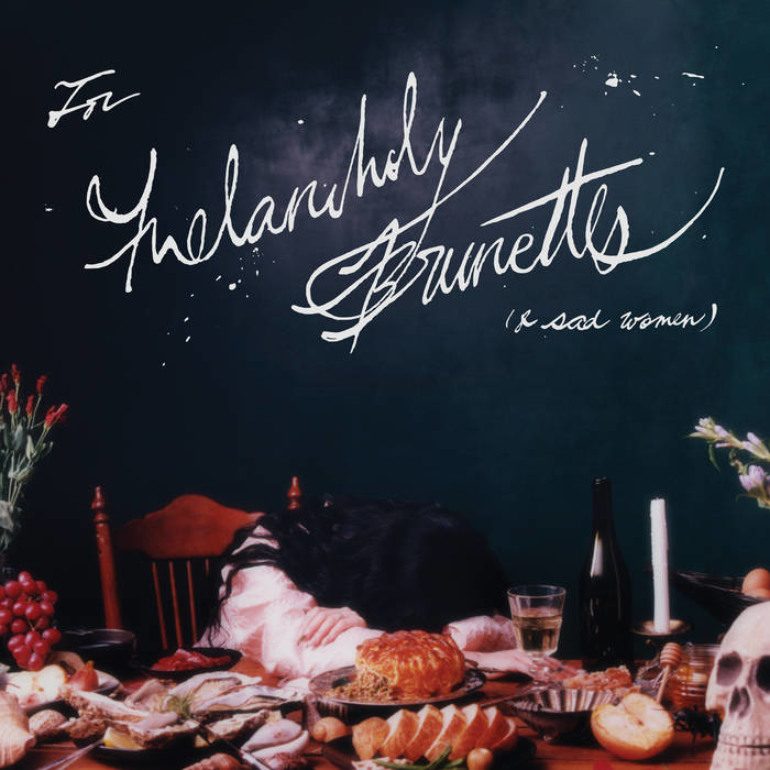

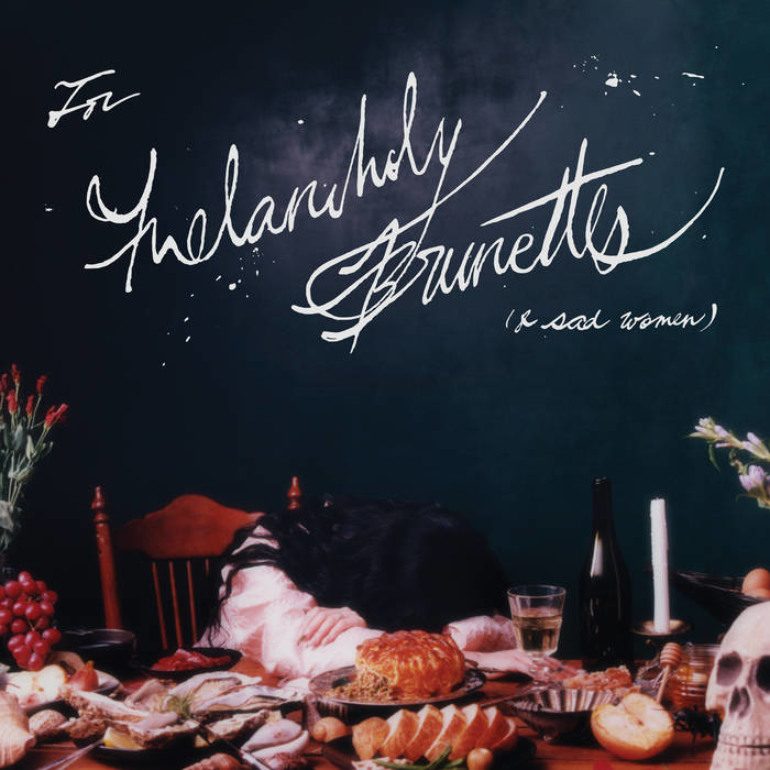

That darker record is For Melancholy Brunettes (& sad women); the night to Jubilee’s day. The record stands fabulously on its own and forms a satisfying set with the rest of Zauner’s discography: a dazzling Rolodex of moods. Zauner has remarkable emotional elasticity, aided by her habit of singing from the POV of a finely rendered character. The result is songs that lead with a sharp, exacting edge of emotion and belie complicated depths beneath. In Jubilee’s “Be Sweet” (indie pop’s very apex), Zauner embodies a “sassy ‘80s woman-of-the-night persona” commanding beaming, grooving, neon synths, and an infectious rhythm. The titular lyric, however, reveals the diva getting high on the thrill of pleading with a spacey partner for devotion. The verses reveal her complicated idea of love: she begs, “Come and get your woman / pacify her rage.” Slide Tackle lays down a groove that would be at home at a hotel pool or a particularly chic Old Navy (complimentary) before Zauner sings “I want to navigate this hate in my heart” and “don’t mind me while I’m tackling this void.”

Melancholy Brunettes is all avatar, with Zauner zeroing in on the spiritually starved male psyche. Internet commenters have dubbed it her “incel album” — she does mention “incel eunuchs” and read Infinite Jest as research — but Zauner’s characters are less loveless than lovelorn. The titular narrator of lead single “Orlando in Love” lives in a Winnebeago RV and is seduced by a siren. Zauner said the “whimsical, foolish male protagonist” set the tone for an album that “is largely about people, often men, who find themselves seduced by temptation and are duly punished for it.”

No kidding: Zauner’s Melancholy Brunettes boys are heavy drinkers and cheaters, “drinking gin at noon and watching ATVs rounding muddy corners.” The material details — country-macho vehicles, booze, and lighter tricks — stand out, as the lyrics might otherwise be Zauner’s most oblique yet; men of few words voice confessions and moods through a prism of literary references. The result isn’t foggy but inviting — like a good book, Melancholy Brunettes feels thick, rewarding of rereads and closer attention.

Literature’s heavy influence — Zauner read boy tomes from Infinite Jest to The Magic Mountain — shines through the dark-romantic production, which glides from fairytale to gothic to Western. Producer Blake Mills’ track record producing Fiona Apple, Perfume Genius, Bob Dylan and Feist is evident: the second single “Mega Circuit” sounds strongly of Apple. Meanwhile rollicking “Picture Window” swings twang rock, “Winter in LA” recalls Clairo, and “Leda” is plaintive, mournful, as if sung on lyre by a tragic Greek poet.

The record’s arc follows the hero’s journey, or perhaps the hero’s crash-out. The striking and romantic opener “Here is Someone” shimmers with finger-picking, strings, woodwinds, and a harp that makes the narrator watching their beloved in the yard seem fairytale-ish. Yet, as in fairytales, darkness bubbles beneath, with references to “last night’s drinks (bringing) on your morning tremors” and “(running) my guts back through the spoke again.” In Melancholy Brunettes, love is enticing and effervescent — yet a road to ruin. By “Little Girl,” our hero is “pissing in the corner of a hotel suite.” By “Men in Bars,” featuring Jeff Bridges, his love has decayed into reminiscing, self-defense (“I was tempted, sure, but I have come home now”) and insisting “we built this, and even when it falls apart it’s ours.” The song was inspired by “Ruby, Don’t Take Your Love to Town,” in which a possessive and despairing Vietnam veteran browbeats his girl while also evoking the Mountain Goats’ anthem of mutually assured destruction, “No Children.”

As it’s objects, Melancholy Brunettes could take the titular melancholy brunettes and sad women as its subjects, the treasure and torment of the disgruntled young men that, as a society, we seem to be hearing so much about. But Zauner’s use of an avatar serves to give voice to a side of the self. Melancholy Brunettes’ airing out of the “male loneliness epidemic” line of emotions lends understanding but also creates breathing room for a universal identification. It turns out that shame (“Winter in LA”), fatalism (“Men in Bars”), and loneliness (“Leda”) are shades of the melancholy brunettes of the world, too.