Now celebrating 28 years as a band, Norwegian metal collective Ulver have had time to reflect on their long musical careers. Since releasing their first album in 1995, the experimental band has jumped seamlessly from style to style, taking the attitude and emotion of black metal and molding it into synth pop, trip hop, progressive rock, and any number of other genres. They’re celebrating 25 years of studio recordings with a book Wolves Evolve: The Ulver Story, a reflective piece featuring old interviews, lyrics, and photographs chronicling the band to date. MXDWN caught up with singer and multi-instrumentalist Kris Rygg to talk about Ulver from the very beginning, tracking their musical evolution over their versatile discography — while also looking to what the future might hold.

mxdwn: You guys have been releasing music for 25 years now, I suppose?

Kris Rygg: If you don’t count the first demo from ’93, yes. Our first album was released in early ’95, though it was recorded in ’94.

mxdwn: So even longer then?

KR: If you counted the very rudimentary beginnings, we actually started in ’92.

mxdwn: Wow. That’s a long time. So thanks for doing this Kris! We wanted to single out some of what we would say major stylistic changes or significant works and then ask you a question or two about each one — maybe about the recording of it, some of the themes there and what it meant to you and the rest of the band. Sound good?

KR: Yeah, sure, I’ll do my best.

mxdwn: First of all I wanted to ask, you’ve clearly had some time to reflect because you guys have put this book together Wolves, right?

KR: That’s true. It might seem strange to say there’s been an upside to this situation [the coronavirus pandemic], but it gave us the breathing space that we kinda needed to finish that book project.

Mxdwn: And what inspired you to put that book together? What was the impetus?

KR: Well, it’s something we’ve talked about on several occasions before. We talked about doing it in many different ways too. For many years we used to write these letters from the band to the world, we had a bit of fun with that. So to begin with we discussed compiling all the different things we’ve written over the years, together with our lyrics and designs, photos — more of a scrapbook project, I guess you could call it. And then we met Tore [Engelsen Espedal], this guy who’s the main editor and narrator of this book. Going back some years before that, there was actually an Italian journalist who started writing a book about the band, but it fell through for various reasons. We were in touch with Adam Parfrey over at Feral House, and there was a fire there, but then it faded. And then nothing happened for years, until we met Tore, who is a very keen writer in his own right, and also had an extensive knowledge of the band. We started talking about it again a couple years ago, with him, and the ball started slowly rolling by recording some interviews and things like that. As to why? I guess now is as good a time as any, as the world crumbles around us.

mxdwn: Cool. Yeah, I can imagine. It’s got to be quite odd though, 28 years, does that not shock you a bit?

KR: *Laughs* It does. In some respects, it’s like if we go back to the beginning of where this book starts — the early ’90s — it doesn’t necessarily seem that long ago to me. But then when you start to think of all the things that have happened since, properly reflect on it and jot it all down, it becomes quite clear that it is a long time. A lot has transpired. This realization that, you know, we are regrettably getting old. You wake up one morning, look in the mirror and woah!

mxdwn: Interesting way of putting it…

KR: It’ll happen to anyone eventually. *Laughs*

mxdwn: Sure, moving on then…Talking about this first studio album, Bergtatt – Et eeventyr i 5 capitler, it translates into “Spellbound: a fairytale in five chapters.” Is that correct?

KR: Well, it’s a translation with some poetic liberty. Literally it means “mountain taken,” which does not quite have the same ring to it in English. It’s a Norwegian expression, which stems from folklore. But in everyday speech it can also mean being spellbound, or bewitched. By nature, for example.

mxdwn: So that record is very dark, black metal. Did you always want to be that kind of band?

KR: Not always. But back then certainly. But we were always into many different things, and I guess we’re still a dark band in many respects. But the form has changed, obviously, over the years. But yeah, back then we were obviously quite taken by this, at that point, small world of black metal — and you know that whole transgressive, anti-modernist, you know… the nature worship and all that stuff. So yeah, at that time, obviously we didn’t know that we would sit here 25, 26 years later and talk about Ulver as an active thing, you know.

mxdwn: So that second album, Kveldssanger then was a bigger stylistic change — a lot of instrumental stuff, even some strings…

KR: Yeah that’s quite a sparse album. Very woodsy, Tolkienesque. Mainly acoustic guitar, some cello, flute, some tympani, and chanting voice. It’s quite dreamy, romantic. The reason we decided to do that? We enjoyed the music, obviously, and particularly Håvard, our guitar player at the time, he had a real penchant for playing this acoustic, folky stuff. But as a band it was also a bit of a statement, as the original idea of black metal was, in a manner of speaking, feeling before form. It kind of belonged to the whole black metal aesthetics even if it didn’t have an ounce of distortion, if you know what I mean. So there was an aspect of making a statement with it, I think. It also had to do with the fact that as a band in a classic rock sense, with two guitars, drums and bass, and vocals — our drummer had to go and do his military service and stuff — we had some time on our hands. So that’s when that idea came about to go and cultivate that acoustic stuff that had only served as brief interludes and such on the first album.

mxdwn: That’s interesting though, because I’d never necessarily thought about it in terms of the feeling rather than the sound for black metal, because it’s such a niche thing — this relatively small subgenre. So it’s quite interesting that you guys were able to look at it like that.

KR: Yeah, that’s how it’s become over time. Not so many years after, black metal became much more recognized… identifiable. It was still a subculture, of course, but a quite popular subculture all of a sudden. You know, a lot of people jumped on the bandwagon. This was sort of initially a small hotbed for ideas that were relatively unheard at the time, all the other ideas in metal were kinda spent and used. So when all these other bands came about, the formula became, well, formulaic. Things started to sound very similar, and obviously in later years, there’s a wide perception of ‘This is how black metal is supposed to sound.’ In the beginning there was quite a lot of focus on going against the grain, in a way, within this world of trebled guitars, fast drumming and shrieking voices, the basic ingredients. But there was a bigger wiggle room within that. We toyed with that basically.

mxdwn: So one of the most (interesting?) albums for me across your discography is Themes from William Blake’s Marriage of Heaven and Hell. Talking about that dichotomy, I think of The Divine Comedy or Paradise Lost. Why William Blake then?

KR: Well, it’s a fantastic text, touching on some themes and things from Dante and Milton, which you mention. It was relevant at the time because it’s a great mystical work, quite simply. It navigates this sort of religious iconography that we’d been toying with in black metal — questioning or negating the Christian worldview. The hypocrisy of the clergy and all that stuff. To me it became a way to make yet another statement, in a way. Not in the terms of black metal, because we were musically moving away from that at the time, but just in terms of aligning oneself with a more nuanced reading of the Bible or a few archetypes… Stereotypes, I guess you could also say.

mxdwn: Interesting… Moving on to the next record I wanted to talk about: Perdition City, which is effectively a ‘trip hop’ record in a sense, right?

KR: Yeah. Maybe more like electronica with a dash of trip hop. But yeah, it’s certainty informed by the trip-hop thing, which was big in sort of ’96, ’97, ’98.

mxdwn: What happened there, then? Why was that the next big stylistic shift for you guys?

KR: By that time we were essentially down to two guys who were making this stuff together: Tore Ylwizaker and myself. And we were very studio-bound, using our studio, sampler, computer and such as a means to create sounds — as opposed to some years before where there was a lot of drums and buzzing guitars and these kinds of things, where the music was born in the rehearsal room. Again, it was sort of a shifting of the scenery of the music, but also our own circumstances and interests. The sounds became more technological, digital, urban. I can’t tell you exactly why that happened, but it had something to do with slowly moving away from this whole black metal outlook — the whole forests and fjords and glorious ancient times shtick — and adapting more to modern life, you know, with all its moral decay and political problems and communication breakdowns.

mxdwn: In a sense did you feel like you’d almost grown out of it?

KR: That’s how we probably felt at the time, yeah. We were a bit over the fantasy thing, I guess, which is of course strongly connected to metal aestheticism — this was 20 years ago, or 21, as Perdition City was made in ’99. And yeah we were listening more or less exclusively to electronic music by this time. And getting more adept at these techniques, I suppose — sampling things, editing and processing sounds, it was more like sound design… soundscaping.

mxdwn: So for the next, Silencing the singing, you moved to an entirely instrumental sound, right?

KR: Yeah, that’s actually two EPs. The first was called Silence Teaches You How to Sing. And the second Silencing the Singing. And then it was released as a compilation called Teachings in Silence. We were going even further into a sort of abstract, nocturnal, glitchy echo chamber, basically. We created those things rather quickly, so it’s a bit more… I wouldn’t say improv, but it’s a bit more happenstance: electronic manipulations and a cut-and-paste-type mentality. Still very much two guys isolated in the studio, obviously smoking lots of weed — being in the zone basically. *Laughs*

mxdwn: Kris, I should know this. You handle the songwriting, or is it split up?

KR: No, no. Not on my own. On the Blake album, for example, Tore Ylwizaker came into the picture and he’s really a wizard when it comes to programming and engineering things, manipulating sound. He’s also a big synth aficionado. He’s a big, big reason why we were able to change our sound so radically with the Blake album. After that album the band up until then kind of disintegrated. Partly because some of the guys had gotten jobs, went a bit more nine-to-five. You know, shifting priorities. During those next few years it was really just Tore and me in the studio making these things together. And then Jørn [H. Sværen] of course joined our processes a little later, even if he had been lurking in the shadows before. So I’m not the only guy behind this, it’s also largely Tore and Jørn. In later years more people have also joined our processes, on stage or in the studio. The last few albums, for example, owe a great deal to Ole Alexander Halstensgård’s creative input. So it’s always been team work.

mxdwn: Absolutely! But I wanted to ask in terms of instrumental records then, what was it like to make an album with no lyrics on it?

KR: For me it was a kind of nice period. I can’t remember why I abandoned singing, which I did for quite a few years there. At the time I just wasn’t about singing or lyrics. I was into finding strange sounds and putting them together and making even stranger sounds — experimenting. So, as you know, lyrics and singing came back into the picture in 2003. And by that time, as I just mentioned, Jørn, an old friend going all the way back to ’91 — and who also for a short time was involved in the black metal scene — became more deeply involved. To this day we always write the lyrics in Ulver together actually.

mxdwn: Cool. So why did you make a soundtrack, then?

KR: Well, I guess our music was moving in a soundtrack direction anyway. And then these guys from Sweden reached out. They had made a short film which happened to be based on a sort of lycanthropic theme which fitted us like hand and glove. So, to us that was obviously very intriguing, and a logical next step. I guess that’s what we did right after those EPs. We went to Stockholm for a week or so, and worked with those guys and then went back to Oslo and worked a bit more on it — not a project that took us a long time. And that’s what became Lyckantropen Themes.

mxdwn: And did you watch the film? I assume you must have seen it with your soundtrack on it?

KR: Yeah we had the film in the workstation actually. We were kind of sound-designing after the images.

mxdwn: And when you saw that film with your music on it, was it a bit strange? What was it like?

KR: *Laughs* No it wasn’t strange. It felt rather, this is silly, cool… We did another film after this, which was a bigger budget thing, not Hollywood budget by any means, but a feature film that was shown in Norwegian cinemas and stuff. It was a bit more elaborate, fleshed out. It reintroduced acoustic things like trumpet and percussion. That soundtrack is moving a bit back into — almost an ECM kind of territory — reintroducing some acoustic instrumentation and things that would blossom more with the next studio album.

mxdwn: Was that kind of a progression into a more maximal or full sound?

KR: Yeah, I think so. I guess Blood Inside is like a reaction to all of these introverted years, this sort of nocturnal isolation tank, which we were in for some years — the Perdition City years I just call them. I think Blood Inside was reacting to that and taking in lots of prog, some flashy rock antics, still insane programming stuff going on and weird samples and things — but also going crazy with lead guitar solos and drums and horns and lots of freaky stuff. It took us a long time to create that album, actually.

mxdwn: Yeah I was going to ask. You said your last couple, you moved through things quite quickly. But then for this one did you feel like you were stretching yourself a bit more?

KR: For Blood Inside, yeah absolutely. I guess we felt it was time to get a bit more ambitious again in a way, ‘go big’, in the same way that the Blake album was quite an ambitious production. So yeah, it’s also got to do with the shifting of musical interests. We started to listen to weird rock music or lots of ethnic, so-called world music, lots of different things — jazz and fusion music and everything under the sun, basically.

mxdwn: Yeah. Therefore making your next album that I wanted to talk about aptly named Shadows of the Sun.

KR: There you go.

mxdwn: That’s probably the most critically acclaimed record you’ve ever released, at least in a wider sphere. You also said at the time that it was one of your most personal records?

KR: Yes. And I think it remains true to this day, and will probably remain so until the day I die.

mxdwn: Wow! Why?

KR: Not just me, I think this is true for the other guys as well… Tore and Jørn. It’s a very sort of internalized thing where I think it just clicked between us. We were sort of riding the same emotional frequencies, so to speak. Lyrically as well it’s quite simple, but kinda surface-simple, because it’s talking about the big things, you know? Fears and family and responsibilities, love and loss. That our time on earth is limited. And I think after that album — which also took us quite a while to complete — it hasn’t been possible to add much to that. Not really necessary. That’s why I usually say it does remain our existential pièce de résistance.

mxdwn: So was there a sense of catharsis to it then? You’ve built up all these fears and that kind of thing and wanted to get it out in the music? Or was it just in the moment?

KR: Well, it reflects a year or two of our lives. This came out in 2007. I’d fathered two children by this time, we were entering a new phase in life. I think it sort of collects a lot of these feelings and atmospheres that we had been hinting at in the electronic music and rock or metal, if you will — even with the acoustic stuff. It’s a synthesis of all of those things coming together in a very bespoke way.

mxdwn: And from there you had a four year hiatus, or four years of not releasing an album under the Ulver name?

KR: Well not a studio album, that’s true. But we certainly did a lot in those four years.

mxdwn: Right, so you had those four years in between albums under that name. Why that gap?

KR: Going back to Shadows. After that album it’s probably fair to say we needed a bit of a break from each other. It’s a quite tense space to be in, in a way. There was probably a year after where we didn’t do much. In 2008 we moved into a new studio, Crystal Canyon, which became this collective place with many bands and many new people. Talk of Ulver becoming a live band started — we didn’t play live in all these years leading up to this. So then by May 2009 we played our first concert after 15 years or so in this big auditorium in Lillehammer, some hours north of Oslo. People came from all over the world. It was a crazy event, really. And that instigated a lot of things, with Daniel O’Sullivan entering the picture as a new member of sorts. At least for some years there. We had started some projects before this; I think we started the Sunn album [a collaborative album called Terrestrials with drone legends Sunn O)))], and Childhood’s End — or the first sessions for that album –– before this live thing happened. But then, we started to play live and that was a big and pretty time-consuming thing around 2009, 2010. In 2010, we did quite a few shows, a big tour. Then we recorded Wars of the Roses which came out in 2011, which was a bit more back to the rock format. It takes in things from psychedelic rock or art rock, Krautrock, Italo disco, not new influences exactly, but some musical avenues we were keen to explore around those times — especially being a live band with guitar and drums and all those things back in the fold again. Then we did another year or so of shows, in 2011.

mxdwn: Being a live band, having to adapt, did that inspire Childhood’s End?

KR: As I said, I believe Childhood’s End was the first thing we started after Shadows of the Sun, before we dove into the touring thing. So yeah, the first tracks for Childhood’s End were actually laid down quite a long time before Wars of the Roses.

mxdwn: And what was putting together that album like? Because it’s a covers album, right?

KR: Yeah, it’s all late ’60s garage, psychedelic rock. Baroque rock. Sunshine pop.

mxdwn: And that was just music you were into at the time?

KR: Well, I had like a 10 year spell of obsessing with that stuff. It’s a reflection of those interests, of course.

mxdwn: And was there a specific song, or specific band you covered, that you’d always wanted to? That you can recall?

KR: No, well I suppose it probably started by talking about covering a Doors song or something from Love’s Forever Changes or something — which never happened! That whole project lasted many years and in the meantime we were out touring and doing different things. I remember picking up obscure psyche vinyls in Vienna or Athens, taking them home and selecting songs from those trips to record shops and things. Just hoarding music memorabilia, nuggets, and then making the selections thereafter.

mxdwn: Cool! And then the next album I wanted to talk about (ATGCLVLSSCAP), I am very unsure how to pronounce…

KR: It’s not possible to pronounce it! I’ve got it memorized as “All the Great Constellations Live Very Long Since Stars Can’t Alter Physics.”

mxdwn: So what’s the significance of that?

KR: It is a mnemonic system, the capital letter of the astrological signs. It’s quite messy, doesn’t really roll off the tongue. It’s our way of being a bit difficult. *Laughs* That’s why we just call it the Zodiac album. It’s a 12-cycle thing. It’s got 12 songs, culled from 12 gigs. It’s a bit pseudo-numerology.

mxdwn: That’s interesting! I was listening through some of these records and had no idea how to pronounce it — so thank you for clearing that up.

KR: I’d love to hear you try.

mxdwn: *laughs* Absolutely not! But you were trying to be a bit difficult or more creative? What was the inspiration?

KR: Not necessarily. More cosmic, maybe? That album is, I guess it was kind of planned, because we did go out on a smaller tour again, in 2014, which was quite improvisational. We had laid out some things — to have something to musically lean on — but a lot of these gigs were very loose and differed from night to night. The whole idea, kind of a backward way to do things, was to record all that happened on that tour and then make a record of it — just because we were enjoying being a live band at that time. In playing many of the songs from Wars for example, we would often stretch out parts of the songs and play them a lot longer, add things that wasn’t necessarily on the album. So we wanted to take that idea further, and also have that added pressure of doing it in front of people — then you have to get your game face on! So there was a bit of pressure there. We didn’t always deliver super tight every night, I will admit to that. But some of those gigs were really good. And I think the vibe of that album couldn’t really come about if it had started in a controlled studio setting. We’d be too tempted to fix this and that, you know. So the sort of looser, more ephemeral feeling is very much a result of the fact that the majority of the sounds there were born in a live, or real-time situation.

mxdwn: Right. And then you said you had this obsession with this late ’60s psychedelic thing. Was that kind of an influence as well? A jam band thing going on?

KR: Yeah, it’s a bit Grateful Dead, in that sense. Sort of tapping into that attitude, recording the moment, the fleeting vibes.

mxdwn: Moving on a bit to 2017, you had the Assassination of Julius Caesar. You’ve described it as your pop album. So why’d you make a pop record?

KR: Because I love pop music! Always have. Not only me, this is something we have talked about for years and years, making something at least more akin to pop. Something more massive, catchy, with unashamed hooks and grooves, you know. I guess of you ask a pop aficionado, they probably wouldn’t call it pure pop. But to us it’s a pop album. It’s the closest we get — this new album is pretty close too. Again, things changed. We moved studios. The Crystal Canyon Studio, we had to move from there. So, again we were back to our old place and we were back down to the core of Tore, Jørn and myself, with Ole Alexander Halstensgård added to the mix. Working less like a rock band again, more in-the-box, as they say. And by that time we’d obviously sort of been — it sounds silly — rocking out for a few years. Wars, Childhood’s End, Zodiac, and all the traveling and concert activity. So it felt like time to shift focus a bit and try and make something a bit more studio-produced, stringent.

mxdwn: One thing that strikes me is this idea of the “dark wave” sound. Was that an influence?

KR: Not personally, no. I think that tag maybe comes from the fact that we have a dark background, you know, in metal or post-punk. I’m not really hearing the dark wave, to be honest… other people hear it though! It is darker-sounding pop music, of course, and created primarily with synths and plug-ins, but I’m not really hearing the so-called synth pop either. *Laughs* To me it’s more Roxy Music, Bryan Ferry, David Bowie or Grace Jones than anything Ultravox or Human League.

mxdwn: Interesting…

KR: To me it’s more…I guess it’s convenient for people who might not normally listen to much pop music, they quickly go “oh, sounds just like Depeche Mode,” and maybe that’s because it’s the first thing that comes to mind, I don’t know –– this darkish pop group that many rock or metal fans can relate to. I’m a bit surprised at just how often that name comes up, because in all honesty, I never listened to Depeche Mode! It’s got synths certainly, and we may dress in black or write about Jesus, but there’s also a lot of acoustic drums and percussion, guitars, violins and violas — it’s not that synth, or wave-y, in the end. But it doesn’t really matter, people can call it what they want to call it.

mxdwn: What’s that like for you then? People say “this is a synth pop record.” What’s your reaction?

KR: Well, to me synth pop is stuff like Pet Shop Boys or Erasure. And it just doesn’t… I’m not really hearing much Pet Shop Boys, you know? To me our pop sensibilities owe more to groups like Tears for Fears or Talk Talk, or older disco… Earth, Wind and Fire, Alan Parsons Project. There’s a fair bit of ‘rock’ in there too, in my head, with a modern pop-productional twist. So to me it’s a bit of a simplification maybe, almost dismissive to call it ‘synth pop.’ But I guess it’s synth-laden and it’s poppy, so sure!

mxdwn: So it’s putting two words together at that point?

KR: Exactly! The path of least resistance.

mxdwn: And this new one, Flowers of Evil, coming out. What was the process for that? Were you sitting around in quarantine? How long has this been in the works for?

KR: The album was actually finished right about when this whole pandemic thing broke loose on the world. Our initial plan was to have it out right before our tour in April, which obviously also got pulled. And then, you know, all of a sudden the world was mental! It didn’t make much sense to release it in the midst of all that. But as I mentioned this gave us a bit more time to work on the book as well. So, yeah, we basically decided to just let it lie for a bit, let things calm down. The world being what it is right now, it’s taken up to now before it’s finally out there.

mxdwn: Sure. Was that a bit strange then, that you’ve just got this album sitting there, that you were ready to put out before a tour?

KR: A little bit! But these are strange times, and it’s not really that uncommon for bands. Especially if bigger bands have some sort of long term strategy to drop things bit by bit, singles, videos. We actually did that, dropped a couple songs and stuff. So I guess it’s not that uncommon to have to wait. For us though, we never waited this long.

mxdwn: I suppose this is my final question then Kris, and probably the most difficult, and I don’t mean to make you feel old here! You talk about 25, 28 years, is there anything coming for you musically, or the rest of the band, for the next 25, 28? Have you thought about the future at all?

KR: We’ve talked about it! At this point it seems kind of difficult to imagine what the future might bring about. After all, it’s looking pretty grim out there! But one thing that this pandemic pause, if we call it that, has given us as a band is more time together, as friends. After finishing Flowers of Evil, when you’ve been in a sort of bubble like that for a year or so, it’s quite common to be a bit fed up with each other and need some time apart. But now, the most natural thing for us has been to get together in the studio, just because of the whole social distancing and all that, you have to keep your friends close, in a way. My closest friends are my band, so we’ve been in the studio just hanging around, playing and recording some things, without really thinking, without any big plan as to what it’s supposed to be or not. That’s where we’re at right now.

mxdwn: But that must be quite liberating in a sense?

KR: It’s actually quite nice. It’s the first time ever in this band where there’s no sense of urgency where you’ll otherwise have this strategy, a timeline, a new album and then a tour cycle. So yeah, you’re quite right. In that sense it’s actually a welcome breathing space after 25 plus years of just grinding on.

mxdwn: On that note Kris, that’s about it in terms of questions from me. Quite a journey through your past there, not unlike your book I suppose!

KR: Yeah! We joke internally about the book being the interview to end all interviews. It’s all in there, basically. Well, not all, but there is a lot of information in there, for those curious.

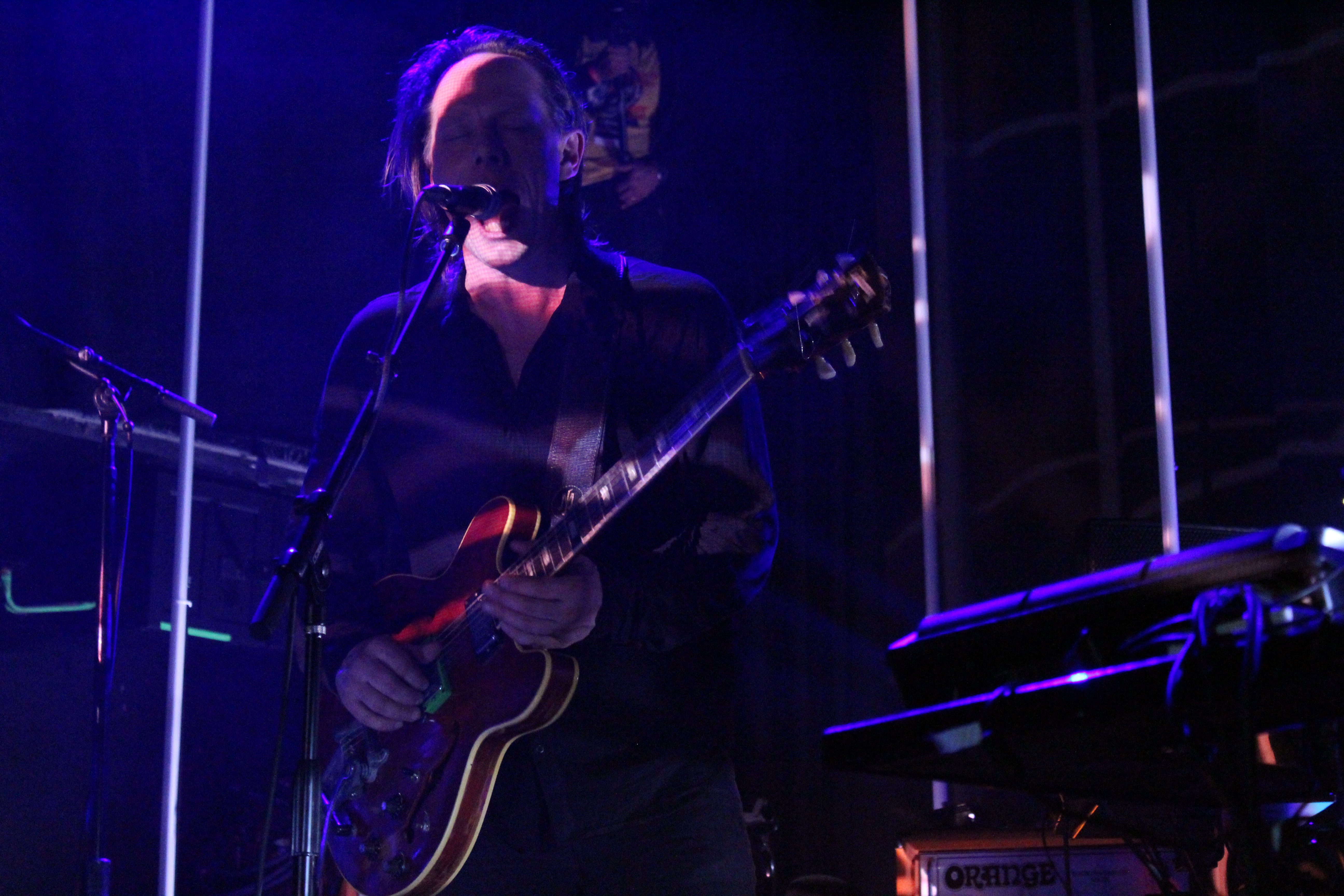

All Photos by Lexi Houghton