Synth dreams of an antique future

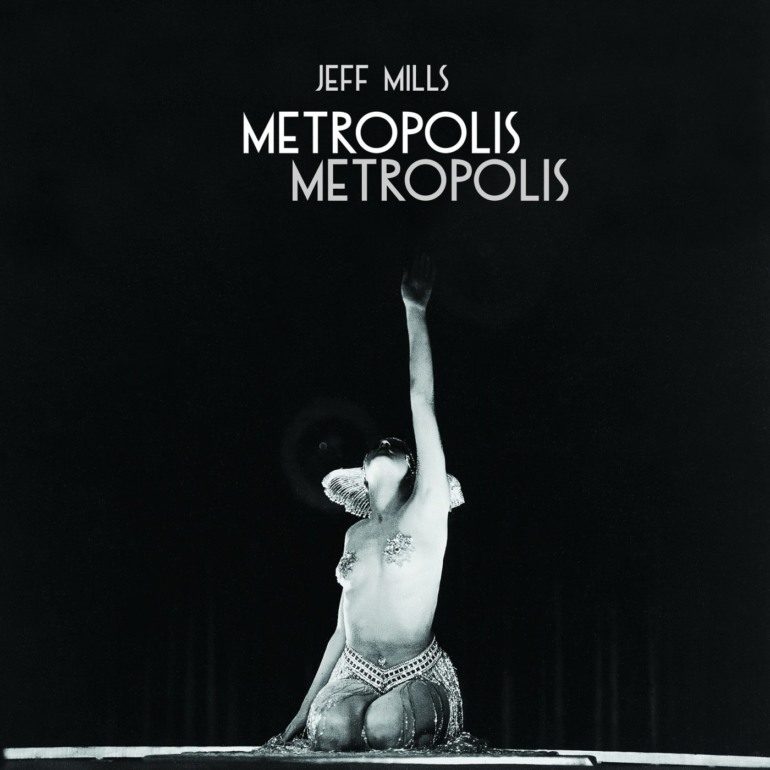

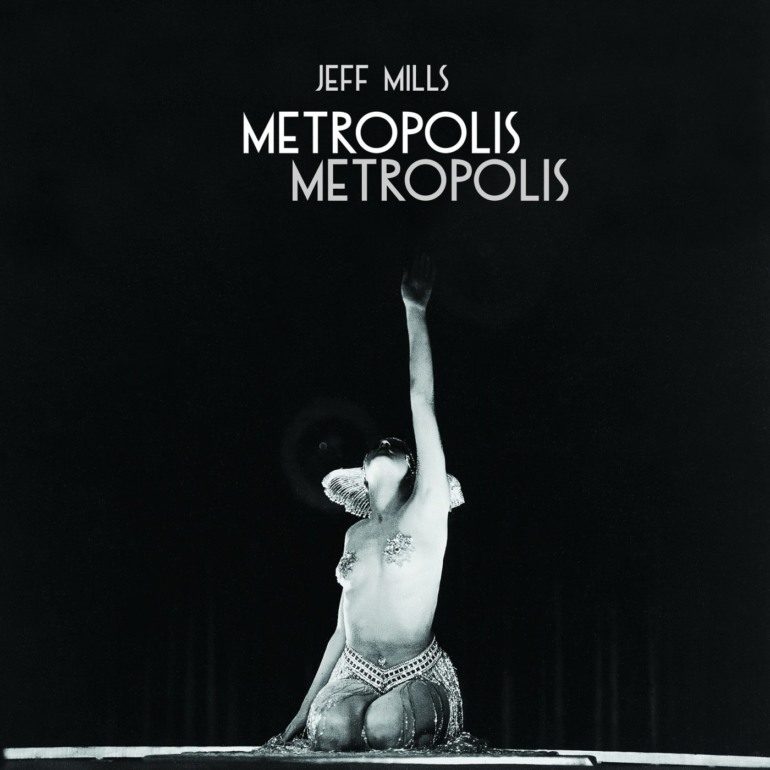

Metropolis Metropolis is the second soundtrack Jeff Mills has released for Fritz Lang’s dystopian silent classic Metropolis (1927). The Detroit born DJ, producer and composer has revisited Metropolis more than 20 years after his first scoring effort for the film. He cherishes Lang’s opus as “a film to be enjoyed, but also noted and examined.” Rather than sync tracks to particular scenes, like he did two decades ago, Mills takes a more evocative approach this time, capturing the dazzling, thought-provoking and uncanny feel of a highly stylized future (present? past?) that was envisioned way back when.

Metropolis’ unabashedly sincere message, which only gets more relevant as the years go by and the mainframes get smarter, appears on screen at the end: “The mediator between the head and the hands must be the heart.” With that burned into his film lover’s consciousness, Mills has composed a mostly electronic tone poem that sounds like a true synthesis between human emotion and mechanical force, rather than cold metal clockwork or a dying A.I.’s inadvertently moving last gasp.

Metropolis Metropolis doesn’t just seem organic because there’s a live drummer in the room contrasting the synthesizer’s faultless replay power and (theoretically) unlimited timbral range with humble mortal time-keeping, delicate snare taps and gentle cymbal punctuations. The audience pictures fingers on the keyboard because the music itself worries, hopes and dreams, rather than merely reminding the listener of those feelings. The looping melodies, electric storm bass lines and birdsong approximations are as angular and dreamy as an alleyway in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. The contorting ostinato that runs through the opening piece “The Masters of Work and Play” is a standout example (perhaps inspired by the scene in the film when the workers rhythmically bend and stretch to pull levers on a brutally high-maintenance machine.)

While Mills’ first Metropolis record was underpinned by a danceable drum and bass groove, the sequel falls somewhere in the Steve Reich zone between symphony and soundscape. It’s too repetitive to be the former, and too intriguing and insistent to be the latter. The percussion is moody not groovy, though there are some bleepy arpeggios and robot riffs that would lend themselves well to breakbeat remixes. The closest the drumming gets to making listeners want to get on their feet is on “Maria and the Impossible Dream.” But the extended bongo solo with trouble-bubbling bass and spidery chimes doesn’t make listeners want to get on their feet and dance—it makes them get on their feet and wander out of the eerie underground labyrinth it sends them into. Naturally, after four or five minutes it segues into muffled snippets of conversation and an idling jet engine hum.

For those who listen as eagerly to “Revolution 9” as any other song on The White Album, this music will cover those expansive moods when listeners want to hear, not quite songs, but the mysterious inner workings of songs. Metropolis Metropolis is a mesmerizing industrial fantasia that deserves to accompany the astounding film that inspired it.