The Keys’ renditions of traditional hill country blues tunes

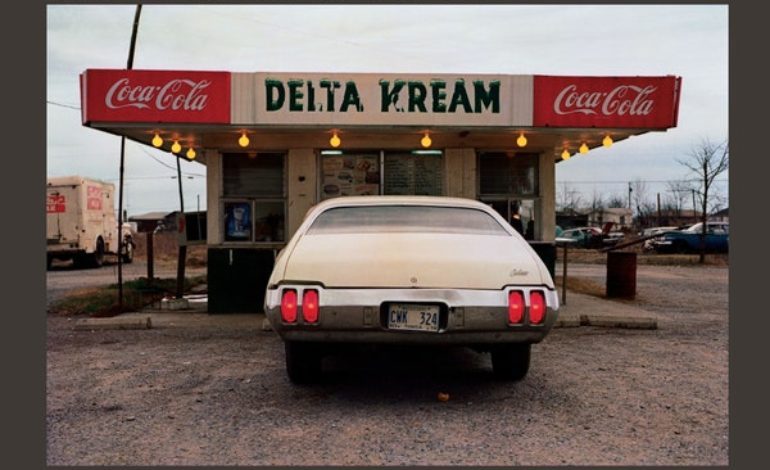

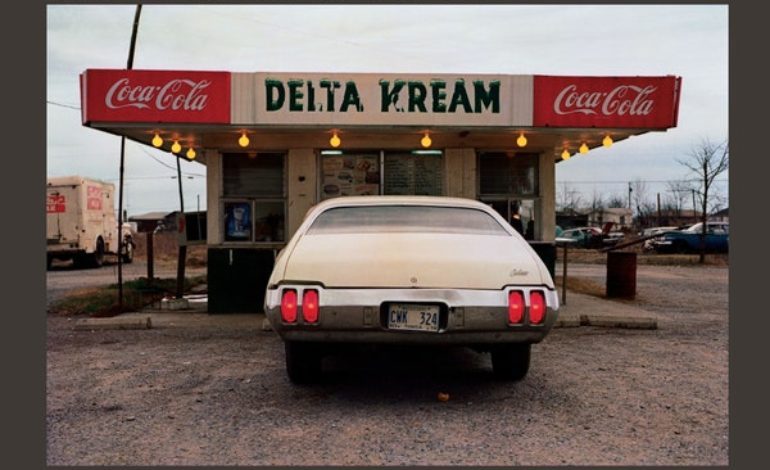

Listening to the blues in the 21st century just reeks of nostalgia and anachronism. It was music that began as early as the ‘10s of the last century, a whole hundred years before now, so its rusty, antiquated aura doesn’t quite jive in its enjambment into the contemporary world. Those sounds spoke something for which we’ve now lost the language. The Black Keys evidently believe otherwise. It seems they couldn’t quite hold in all that seething ardor for what made rock ’n’ roll itself possible, so what better way of honoring rock ’n’ roll’s precursor than to cover its most essential songs? Two years from their electrifying ninth studio LP, Let’s Rock, the garage-blues duo play the hill country blues classics in their tenth LP, Delta Kream.

It kicks off with the ubiquitous “Crawling Kingsnake,” the legendary Delta blues song that supposedly pre-existed any recordings of it, though John Lee Hooker’s rendition is one of the (first) most well-known (aside from The Doors’ lascivious version from L.A. Woman). The Black Keys’ is now the most recent. It honors it well—and keeping in the pastiche spirit of the blues, with their own touch—inducting them into the multigenerational string of musicians who ever dared to recolor it, continuing its legacy 100 years after its birth for the next cycle of renditions.

It seems the act of continuing the blues tradition throughout the ages is a homage to the very process of keeping them alive, similar to Junior Kimbrough, the Keys’ favorite bluesman, whose covers appear on the album (“Stay All Night” and “Do the Romp”) as well as sporadically across their previous output and even in an entire tribute album dedicated to him. Unlike many musicians in the early ‘90s, Kimbrough was keeping the blues alive by composing his own originals when dance music, pop and hip-hop were on the rise, forms of music that adopted an ideology of novelty over tradition.

In the post-millennia, blues popularity is increasingly diminishing, being outshone by the saturation of pop music so that now playing the blues becomes, for some, like reanimating a dead corpse, and for others, like The Black Keys, it preserves the tradition and its mythos. They resuscitate R.L. Burnside’s “Going Down South” from its original recording in 1969 and “Poor Boy A Long Way From Home,” Burnside’s version of the traditional blues song “Poor Boy Blues” by Sam Butler—putatively one of the known oldest; and Mississippi Fred Mcdowell’s “Louise” from 1964.

Actually, come to think of it, that may be a latent function of re-recording songs like the ones off Delta Kream—reconstituting the songs’ relevance and its folklore, persisting by an urge for its perpetuity. The songs almost live in and of themselves. The Black Keys just happen to be the mediums this cycle around.