Genre-hopping, Roots, Revival, Soul.

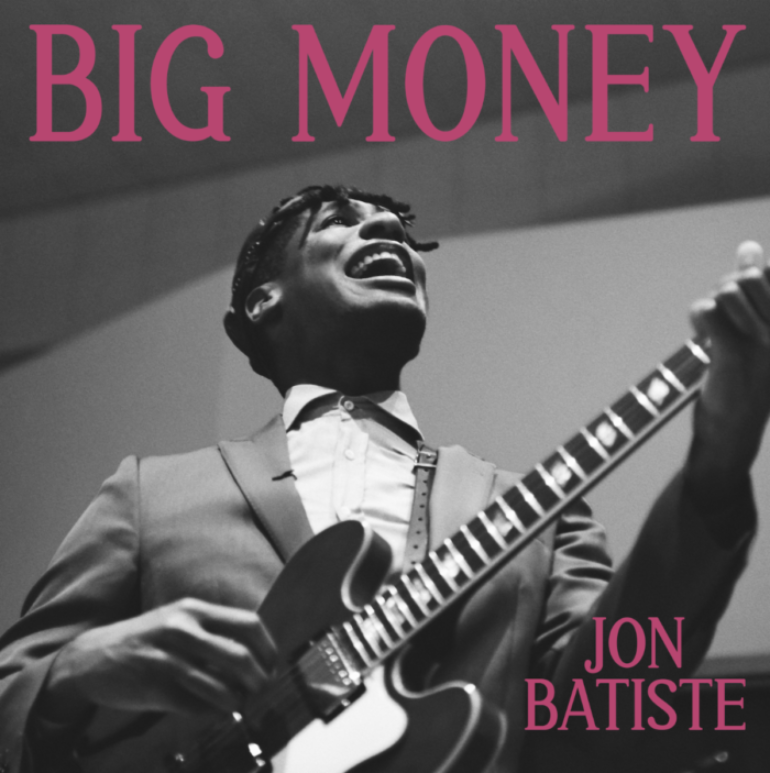

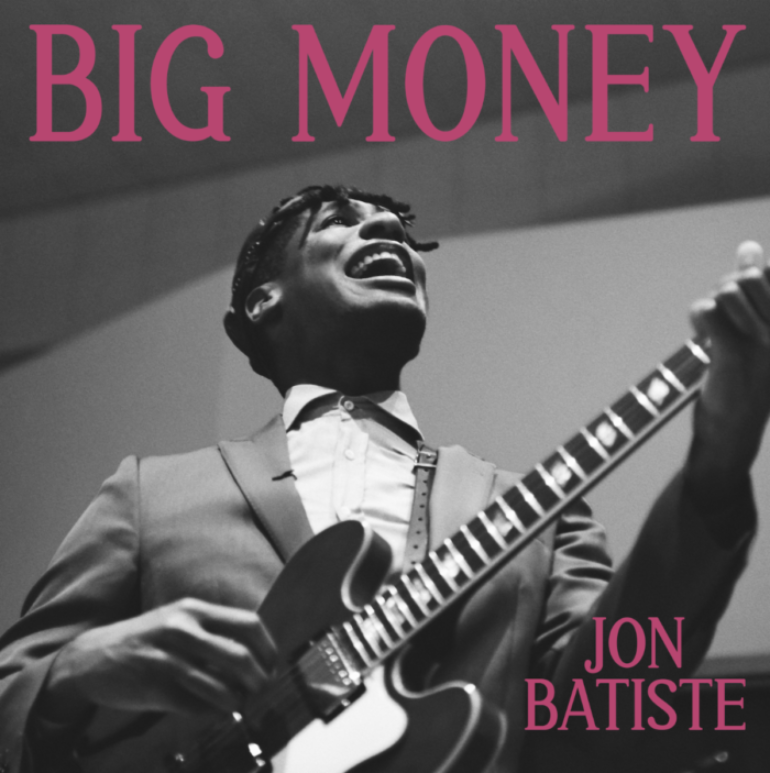

Jon Batiste’s album, Big Money, released Aug. 22 through Verve Records and Interscope Records, explores a fusion of American musical traditions. With just nine songs around 32 minutes in length, the album strips down to to focus on raw performance and honest storytelling, anchored in Batiste’s deep command of gospel, blues, funk, soul and reggae. The project showcases both a communal spontaneity and thematic cohesion, drawing on Americana influences while collaborating with artists like Randy Newman, Andra Day and producer No I.D.

Big Money is Batiste’s ninth studio album and was recorded mostly live over two weeks. Sessions emphasized single-take performances and natural ensemble interplay (via Vents Magazine). The album arrives under exclusive license from Verve Label Group through Naht Jona LLC. Certain vinyl pressings list Decca as the label (via Presto Music).

The nine-song tracklist includes “Lean on My Love,” featuring Andra Day, the title track “Big Money,” “Lonely Avenue,” featuring Randy Newman, “Petrichor,” “Do It All Again,” “Pinnacle,” “At All,” “Maybe” and “Angels,” which features No I.D. and Billy Bob Bo Bob (via Paste Magazine).

The album’s lead single “Big Money” serves as a thematic centerpiece. It pairs infectious rhythms with lyrics that subtly critique blind ambition and greed. The call-and-response chorus recalls the spirit of revivalist soul, while a syncopated guitar groove drives the momentum not just for the song but also the album. The Womack Sisters contribute gospel-style backing vocals that elevate the song’s celebratory surface (via Live Music Blog).

“Lean on My Love” is a funk-driven duet that channels Prince and Sly Stone. Batiste and Day trade melodies over syncopated beats and radiant brass sections. The arrangement’s buoyant energy supports lyrics about solidarity and emotional strength, creating an accessible yet musically layered experience (via Associated Press).

“Lonely Avenue,” a duet with Randy Newman, shifts the tone into stripped-down ballad territory. Over solo piano, the two vocalists contrast sharply—Newman’s gravelly tone playing off Batiste’s smooth delivery. The track, originally written by Doc Pomus, is rendered with irony and warmth. The Associated Press reports that this blues-laced track lands as one of the most emotionally resonant moments on the album.

Batiste dives deeper into existential territory with “Maybe,” a jazz-tinged piano ballad layered with introspective lyrics—“Maybe we should all just take a collective pause”—and improvisational chord voicings. The song’s harmonic style nods to Jelly Roll Morton and early New Orleans’ jazz traditions (via AP).

“Pinnacle” stands out for its upbeat tempo and playful rhythmic structure. Featuring lines like “Hop scotch / Double Dutchie,” it channels a loose, almost improvisational feel. Its blues-based progression and dusty groove bring a juke joint vibe into modern focus (via AP).

“Do It All Again” and “Angels” close the album with soul-searching warmth. “Do It All Again” serves as a heartfelt ballad that reads equally well as romantic or spiritual. “Angels,” with its subtle reggae sway and ethereal melodies, rounds out the album with a calm, contemplative note (via AP).

Batiste, born in Metairie, La., is a Juilliard-trained multi-instrumentalist, composer and bandleader. He is known for his work as the bandleader on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert and for his Oscar-, Grammy- and BAFTA-winning work on the score for Soul. With Big Money, Batiste leans away from the high-gloss production of previous releases like World Music Radio and instead focuses on live performance and stripped-back textures.

According to Times Union, Batiste describes the record as a “New Americana” statement—reaching across genres, regions and time periods to bring together a distinctly American sound. From Delta blues grooves to gospel harmonies and funky brass, the album bridges history with modern storytelling.

Each track prioritizes emotional resonance over studio perfection. Through intimate performances and carefully crafted arrangements, Big Money becomes a statement of both resistance and joy—reaffirming Batiste’s role as a contemporary steward of American music.