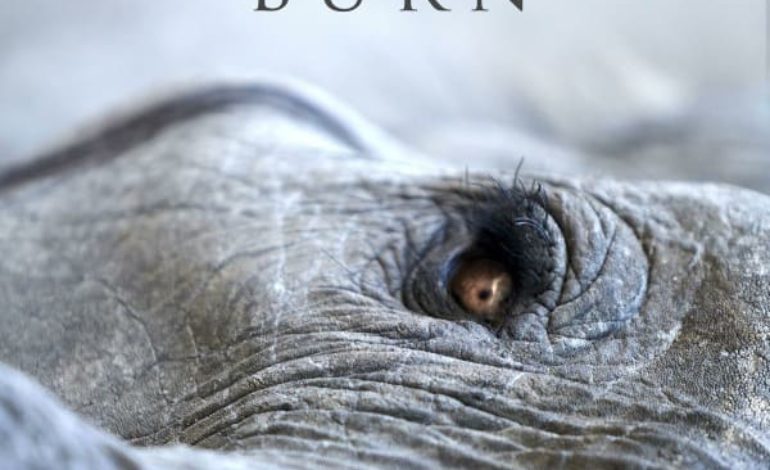

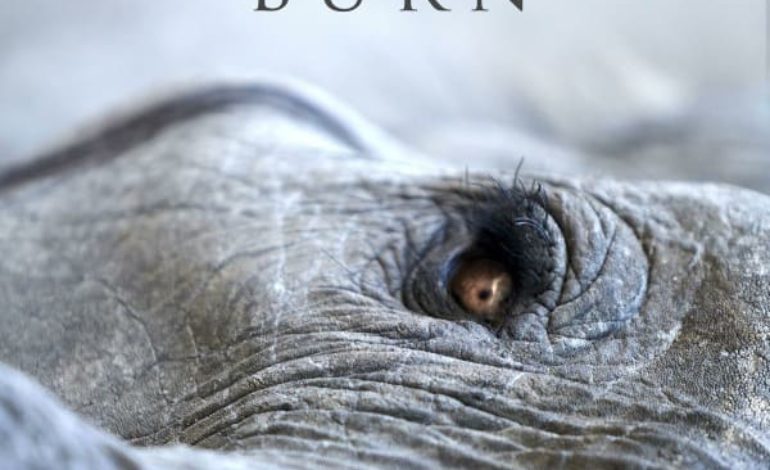

Dead Can Dance members pair up for a collection of vast neo-classical/World soundscapes

Lisa Gerrard & Jules Maxwell met seven or so years ago. Before their meeting, Gerrard belonged to Dead Can Dance, and Maxwell was a theatre composer who then joined the project as a live keyboard player. They went on to collaborate on a song (“Rising of the Moon”) and since then have been locked in a creative bond. In 2015, Maxwell was consigned to produce some music for the Bulgarian choir, Le Mystère des Voix Bulgares, and hit up Gerrard for some help on the project. They held on to a few of the songs and consulted the producer James Chapman a year later. The three then fleshed out some more tracks, and Burn was issued forth into the world under the duo’s new prosaic guise. Each song channels a vast, cinematic soundscape for Gerrard’s operatic litanies to inhabit.

But maybe there’s more insight to be extracted from the co-creators themselves. Chapman and Gerrard each give their own pithy rundowns of each track, and it presents an interesting dichotomy that almost reviews the work itself in the median of two perspectives – sort of like show-and-tell, but it’s asynchronous and outsourced into this. Call it “found” critique, or “auto-critique.” Chapman goes by way of the audio-analytical approach, of course, since he produced it, while the musician Gerrard describes it as an artist might: in pseudo-spiritual abstractions.

For example, for the last song on the album, “Do So Yol (Gather The Wind),” Chapman provides some liner-note context surrounding the song’s making: “[it] was the first track we worked on together, and I love the fact that it is the final track on the album. It became both the beginning and the end of what was a wonderful journey for me. It is joyful, playful and an uplifting end to the album.” Whereas Gerrard proclaims it “a return to the elements, spreading the seeds of lessons learnt with a merry heart.” Yeah, Chapman, you ignorant boor, it wasn’t just a full circle that naturally developed inside the making of the music, it was a cosmic parable. Egad. In actuality, it’s one of the best off the album. It’s got some xylophonic flourishes and a swinging melody that opens up wide as the sky, exultant and shining, the percussion beats like a half-dozen successive door knocks, cymbal crashes showering from above—all within a simple, balanced scheme, neither overzealous nor rudimentary.

Another one: Chapman describes in his technical parlance the fourth track “Aldavyeem (A Time To Dance)” as “one of my favourites on the album. The 7/8 time signature really creates the feeling that the rhythm is constantly evolving, but it also has a groove that connects with the soul.” Of course, Gerrard’s abstruse description counterbalances to give both sides of the song from artist and producer, mage and maker: “a gentle trance which wakes up the sleeper.” Both are right in their own way. The track seems to tumble and gently careen ever-forward, only letting open a hole in its path with a bridge of vocals rendered lightyears away, tethered only by a gentle rolling arpeggio. It begins to make sense what all the songs share.

Most songs play like a neo-classical lullaby, the neo- coming from its use of august synths and its dance-derived percussion. In “Deshta (Forever)” there’s a slightly traditional Middle-Eastern element in the melody, and, in accord with its electronic bass percussion, it wouldn’t be out of place in a ‘90s James Bond opening credits sequence, while “Noyalain (Burn)” flirts with trip-hop tropes through a hip-hop beat and a backgrounded otherworldly chant; both are somnolent and hypnagogic like what one might imagine just before entering the sleep cycle.

Each song off Burn is like being on a soporific, especially if all taken in succession as they drift into each other, each instilling an enveloping and seamless calm. But it’s a double-edged sword. Just as much as it can chill you out, it can also more easily de-stimulate into bored sleepiness, prematurely ending the experience with a nod-off. Either way, it certainly soothes.