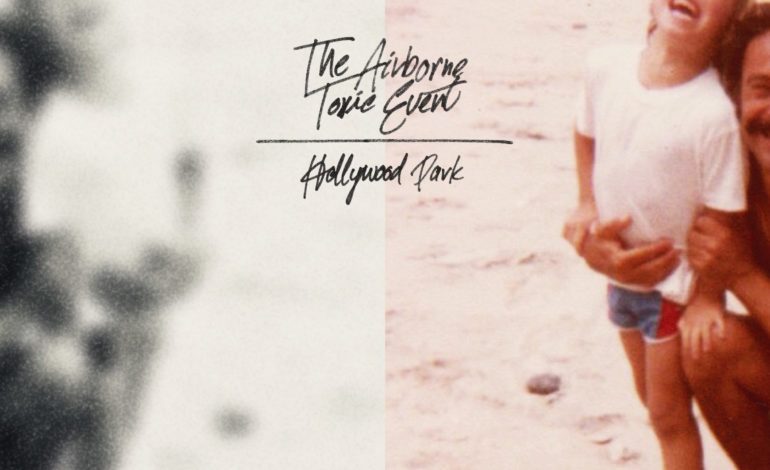

An inconsistent, but deeply emotional life exploration

Mikel Jollett has led a truly remarkable life. He was born into a well-known and violent cult, and he grew up surrounded by addiction, manipulation and genuine pain before founding his band, The Airborne Toxic Event. The group’s most recent release, Hollywood Park, is a distillation of the self-exploration, confusion and agony that came as a result of this incredibly damaging upbringing. For the most part, it’s a truly affecting look at how one man turned his greatest pain and the worst of circumstances into a rewarding and spiritually healthy life. The album’s only weakness lies in its inconsistent writing.

In any art form, it can be extremely difficult to achieve a conceptually tight work. This can be made even more difficult when the goal is the breakdown of decades of reflection over one’s past. It requires a deeply incisive ear and an ability to “kill one’s darlings,” to which this process is often referred as. Most of Hollywood Park is made up of excellent ideas and very emotional chunks of songwriting that just haven’t been pared down to what’s absolutely necessary. For example, the title track opens the album beautifully, but it feels much too generous in terms of length. Jollett’s metaphors are largely hit or miss and sometimes don’t blend well with his more grounded, and generally more impactful, anecdotes.

The case is different with “Brother, How Was the War?,” where Jollett’s impassioned vocal performance, the sparing intro and personal details lend themselves well to the uncertainty that the track explores. “Carry Me,” “Come on Out” and “I Don’t Want to Be Here Anymore” then fall into a pattern similar to the title track. They lack the specificity, fervor and matching instrumental emotion that made a track like “Brother, How Was the War?” great. Simply put, they share similar content, but nowhere near the same level of impact.

The second half of the album is characterized primarily by a lighter sound. It feels as if these songs are closer to Jollett’s current state of hopefulness for the future. There’s an awareness and understanding of how his abuse has affected the fabric of his existence, but that pain is overpowered by his thankfulness for the love and happiness that he now sees can fill his life. “The Common Touch” is a highlight of the album, and the horn section near the end stands out as possibly the most life-affirming moment. This is where this collection of songs becomes an album, despite the frustrating periods of filler that dull the blunt force of Jollett’s potent and personal reflections.

It can be tough to review an album like Hollywood Park. It’s clear that the content of this album is drawn directly from experiences that Jollett might want to forget, and therefore, it should be handled with the utmost respect. Unfortunately, much of the issues with the project lie in how these experiences are presented. Jollett has plenty to say and more than enough affecting stories, but when the band’s music runs a bit too long, or lacks the self-assuredness, strength and precision of the album’s best moments, the impact that sharing these experiences should make is obstructed. If Jollett’s exploration of his childhood is ever the focus of another The Airborne Toxic Event album, a greater focus on refinement might help relay his suffering-riddled childhood in a more compelling way.