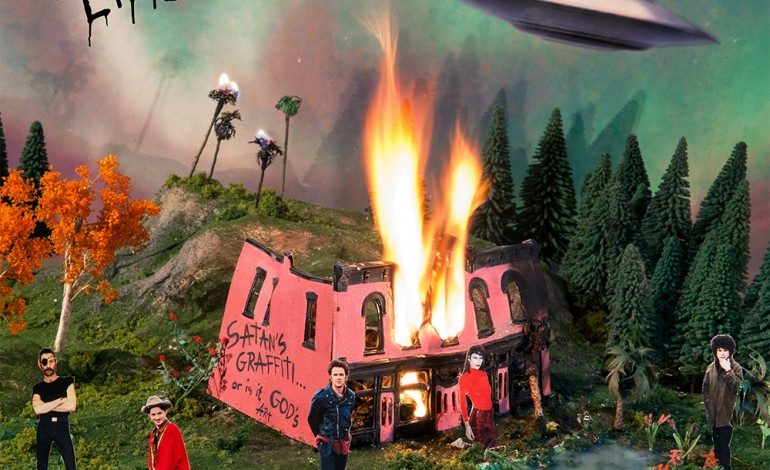

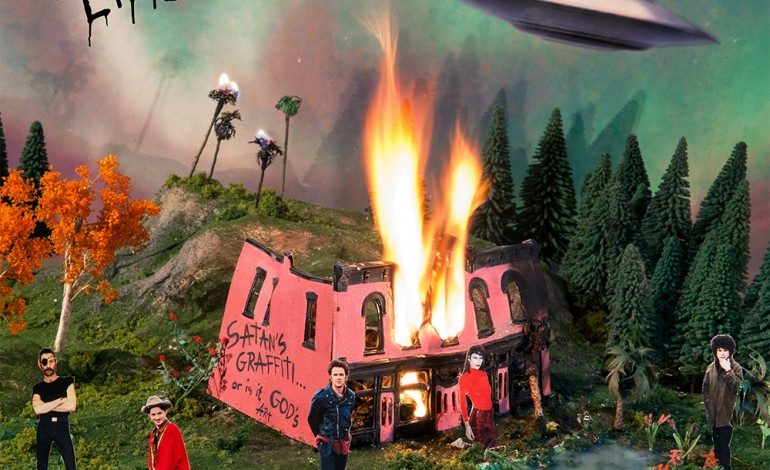

Who’s Up For A Psych Exam?

“Satan’s graffiti or God’s art” is the Rorschach-interpretable question asked by the Atlanta-based garage rock band, Black Lips. Composed of wide-ranging and often contrasting musical and cultural influences, their new album makes it quite challenging for one to provide a clear-cut answer to the elusive question. The 18-track LP displays the eclecticism and countercultural sentiment of “Fuck the authority” that often characterize garage rock music. Dabbling in jazz, reggae, rock, metal, oldies, the band even occasionally bring in a harp-like string instrument on a few songs. The sharp notes, slowly produced by plucking each string, convey a hedonistic, occult feeling due to the sounds’ hinting of Oriental/African tribal cultures. At the same time, the album also brings back something more domestic and homey. After all, garage bands arose during a time when young adults, nurtured in the safe environments of the West, started questioning their parents and instead found inspiration from popular rock bands that were frequent targets of government censorship. So many of the songs are about simple, everyday emotions like falling in love or having hearts broken. Yet, at the same time, given the well-known drug culture that is a marker of the countercultural period and a feature embraced by many garage rock bands, one can’t help but question whether the feeling of euphoria from falling in love actually alludes to being high on drugs. So, Satan’s graffiti or God’s art?

The band herald their eclecticism with their opening song, “Overture: Sunday Morning,” which features a blend of punk rock and jazz. This is followed by “Occidental Front,” in which listeners are bombarded with unintelligible screams and quick drum tempos. The indiscernible noises are a recurring feature, and “Interlude: Got Me All Alone” also presents slurred, garbled speech, vocalized in stretched-out, protracted intervals, almost like words spoken during a drunken haze when time slows down. In “Can’t Hold On,” a harp-like instrument draws up a relaxed, dreamlike atmosphere, like lounging in a harem while hallucinating about floating paisleys. References to the Orient return in “Interlude: Bongos Baby” — except maybe closer to the Middle Eastern or African regions — as one hears what appear like tribal folk songs. Perhaps this fascination with indigenous cultures is similar to the reason why university curriculums saw a rise in ethnic studies during the later phase of countercultural revolution, along with rise of feminism. Or it could be that the desires to get to the marrow, to be raw and to return to the primitive are what drew the band toward other cultures considered untainted by civilization. This mixing of different elements, at times, seems incoherent, but each song feels as if it has multiple lives.

On a closer-to-home note, the band also have something to say. The term “garage rock band” denotes amateur musicians who practice in their parents’ garages. Black Lips try to show that aspect of their members’ lives. Tracks like “Crystal Night” and “The Last Cul De Sac” reminisce on simpler times, of falling in love and broken hearts. “Cul De Sac” concocts memories of Saturday nights when the neighborhood kids would hang out on the house at the “last cul de sac” and meet girls there, sneaking in their parents’ beers. Yet, amateurs eventually grow into professionals, and Black Lips sing of the pitfalls of fame. In “Wayne,” vocalist Cole Alexander affirms, “You did it for the fame,” which leads before, “You never were the same.” Fame changes people, sometimes for worse. Sounding like a country song, “Wayne” again proves just how extensive Black Lips’ eclecticism is. Like “Wayne,” “Loser’s Lament” also exhibits a country style tone and similarly warns about fame’s downsides. It asserts that, “When a boy becomes a man, he has to make his final stance.” Yet, ultimately the drive “to make his final stance” becomes detrimental as “he died without a friend to honor.” These lines seem to be in reference to the band’s switch-up of members over the years. The desire for fame is what pulls them together in the first place but also what pushes them apart towards the end.

Although raw, intuitive emotions like love and desire are what drive the band’s creative energy, drugs could also ignite the same ardor and intensity. On the surface, “Crystal Night” could be about the pains of losing a girl named Crystal; or it could literally be about the pains of withdrawal from crystal meth. One can’t help but place the song in the background of scenes from Breaking Bad in which Walter and Jesse are cooking the meth together. “In My Mind There’s A Dream,” the lines “I beg you on my knees” and “I gotta have you please” are not necessarily pleas to a girl to come back, but aching longings for the next hit, the next high. The album ends with “Finale: Sunday Mourning.” In the song, Saul, a character, narrates about encountering these “magic beans.” And the song ends with dreamy, choral singing of “la la la.” It seems Saul took the magic beans and went off on his psychedelic adventure.

Although the album can be incoherent and absurd at times, perhaps the point is that the band want the listeners not to seek out a point but just absorb what is played. To repeat a clichéd and oft-repeated saying: “The journey is more important than the destination.” The question “Satan’s Graffiti or God’s Art?” suddenly doesn’t seem all that important anymore. Rather, one should just enjoy the adventure and forget about labeling what is art and what isn’t.