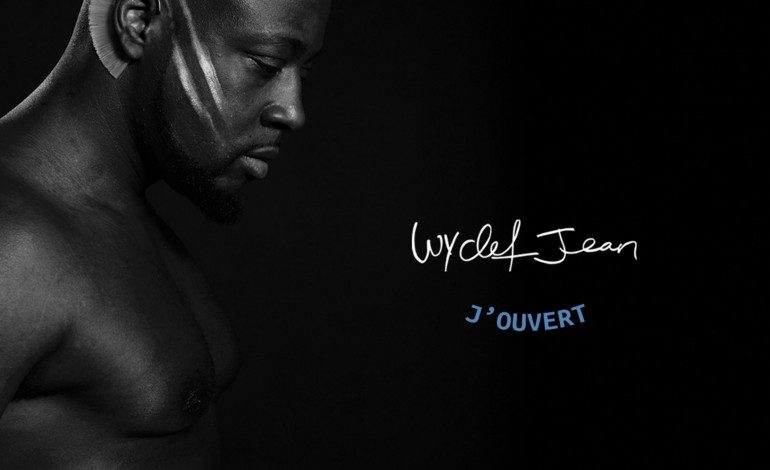

Wyclef Jean’s Trap-Hop Resurgence

“It’s been seven years, man. I left at the height of my career, man. It don’t matter what I did before; it’s the music business, man. You’re only as hot as your last hit.”

Wyclef Jean opens his latest record, J’ouvert, with these words. And, though Jean’s verbiage is less than poetic, these words ring true – so true, in fact, that it seems Wyclef has made an effort to cement himself in the sounds and trends of the current day. Known for his integration of Haitian and American rhythms and sonic cues, Jean instead chooses to defer to the sounds of present day urbanity in J’ouvert. For a record named after a traditional Caribbean street festival, there is little included that trends Caribbean besides an occasional timbale sample (the stellar bass line of “Lady Haiti” notwithstanding); the remainder begs parallels instead with Migos or Young Thug (who is, not coincidentally, featured on the album).

Though Wyclef Jean has never been revered for his depth of concept or vocabulary, J’ouvert pushes few boundaries lyrically. Further, the brazen clumsiness of the final two songs – the socially-minded “Life Matters” and “If I Was President 2016” – comes as a surprise from a man who has consistently prided himself in his socio-political involvement and who has, in fact, very literally run for president (of Haiti in 2010). The sentiment of these tracks may be positive, but what makes the lyrics so utterly cringe-worthy is the thinness of the veil of this very sentiment. With lyrics as brash as these (“Black life matters, police life matters…Harambe life matters”), one must consider whether the aim of these songs is to enact social change, or simply to profit off of it.

In Eric Beall’s 2009 opus on D.I.Y. songwriting, The Billboard Guide to Writing and Producing Songs That Sell, he remarks on the trends established throughout the history of music economization, particularly as they relate to success over time. Beall notes that certain songs come along that take risks, songs that subtly diverge from the status quo (as in “Gangnam Style,” “Somebody That I Used To Know” or even Wyclef’s “Sweetest Girl”). History has shone a light on the slough of facsimile that soon follows the success of these songs, borrowing the certain trait or feature that catapulted the original to the top of the charts. The newer songs, though hypothetically achieving momentary celebrity, seldom approach the degree of timeless appeal that the original maintains.

It would not come as a surprise if the catchier cuts from this record – “I Swear,” “Holding On The Edge” or “The Ring,” to be specific – made their way onto the radio. However, whether these songs have any sustained life in the creative conscious of Jean’s fanbase is yet to be determined.

With a touch of precognition, though, one might guess that such a lasting impression is doubtful. Indeed, one might guess that J’ouvert is more likely to come and go without great disturbance or nuance – to fade into the present sea of auto-tuned, semi-trap facsimile.