Ambition Without Exertion

The timeline of recorded music reveals a history of waves and patterns in the industry’s market. Most recently, while singles and hit-song culture dominated the first decade of the ’00s, the last few years have seen the resurgence of the concept album. From Beyonce to Sufjan Stevens to Sturgill Simpson (2017’s unexpected Grammys sweetheart), musicians and artists have embraced the 21st Century Concept Album as an antidote for the ADD of Vine, Facebook and meme culture.

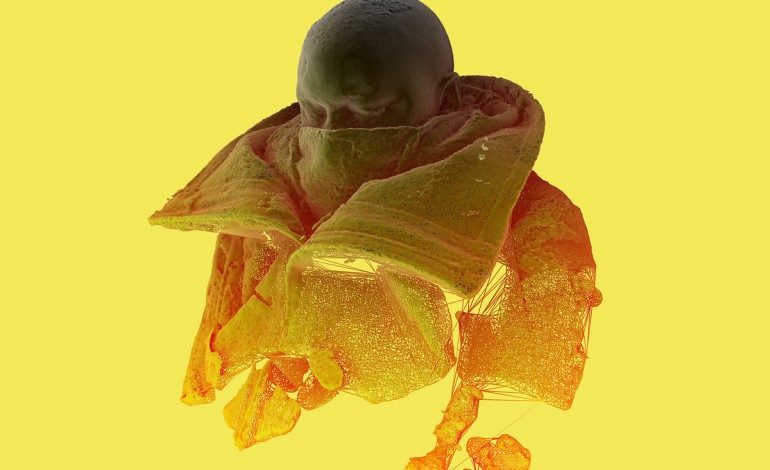

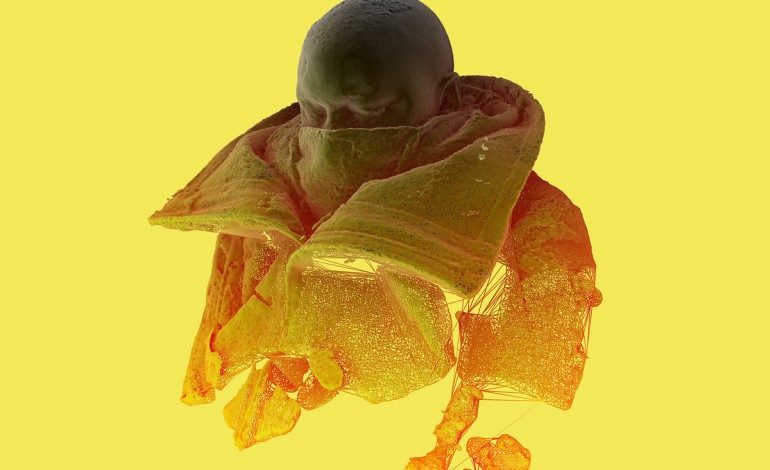

Minneapolis’s hometown hero and Doomtree co-founder, P.O.S, has ventured into this very formula with his newest release. The record, cheekily titled Chill, dummy, comes frustratingly close to creating interest with experimentation, but shimmies around the border of this precipice throughout, never committing to the fissure within. The record assuredly includes well-crafted moments, and these moments can be found scattered throughout. In the end, though, Chill, dummy simply lacks the power to carry itself, and the beige outweighs the interwoven moments of saturation.

Like a good recipe realized with mediocre ingredients, Chill, dummy does all of the things that a 21st Century Concept Album must, but to minimal effect: it toys with atonality, it uses song fragments to delineate form (e.g. the rudimentary “Get Ate” and the melodic “Lanes”), it delves into and confronts social issues. However, for a record that wants so badly to be taken seriously, Chill, dummy strays too frequently and too drastically in both content and style. As P.O.S dons a series of hats in quick succession, none feel truly authentic. “Wearing A Bear” dances over a retro drum loop and sampled vocals, finding P.O.S resembling a less-poignant Xerox of his Rhymesayers label-mate Brother Ali. Directly following is the histrionically dark “Bully,” a song that absorbs techniques frequently tapped by MellowHype and Tyler, the Creator. While P.O.S’s ability as an emcee is undeniable, such a disparate approach begs the question – what is Chill, dummy aiming to accomplish? Is there a mission statement here? If so, how does it self-unite amongst such a collage of soundscapes?

P.O.S is at his best when pushing past the binary of the expected rap lyric, for which he certainly has the capacity. Non-ironic self-reflection finds him at his best, and for an emcee known for creative sentence structure and allegory, P.O.S pulls out the stops at key moments. Speaking on his 2014 kidney transplant in “sleepdrone/superposition,” he examines the post-op emotions of writing a thank you note for his friend’s support, and the internal implications of these very feelings (“when I wrote it, I felt nothing but the numbing of cliché/it tasted nothin’ but batteries and iron all over my tongue,” he quips). However, even within this one song, the lyrics are hardly a home run; it is hard to imagine verses that shift artfully from the topic of “Eric Garner” to “pre-cum,” and P.O.S. has unfortunately not found the answer in “sleepdrone/superposition.”

All of this being said, “sleepdrone/superposition” undoubtedly cements itself musically as one of the stronger cuts on the album, along with the contextually similar “Pieces/Ruins.” These songs allow themselves to play with drones, vocal sampling and panning, taking risks otherwise avoided throughout the album. Of note are the saw-wave bass and overdrive-soaked drum programming, filling out the extremities of the sonic spectrum in a manner strikingly reminiscent of Dave Sitek’s work on TV On The Radio’s 2004 LP debut, Desperate Youth, Bloodthirsty Babes. P.O.S and producer Joe Mabbott, however, largely forego one integral feature of Sitek’s production on these early TVOTR releases, one that grounds the musical drama in realism – acoustic instrumentation.

In the VICE documentary Noisey Atlanta, Migos members Quavo and Takeoff show the film crew their home studio: an empty closet, containing nothing but a microphone and a portrait of Tupac. “I bet y’all thought you were gonna see a big mixing board, something crazy,” Quavo reckons. “Nah – that’s all we got. That’s all we need.” And for Migos’ bass-pounding trap hits, it appears that he is correct.

Chill, dummy, meanwhile, proudly declares that much of it was recorded at “Stef’s house,” “BJ’s house” and “Gerald’s house,” and the programmed electro-centricity of this home studio approach is more than evident. Synthesizers, sine bass and quantized drums dominate the record, united in their canned tone. Truth be told, the recent rise of the SoundCloud celebrity has given certain validity to these sounds (though many such producers – the likes of Gramatik, Chrome Sparks and Jonah Baseball – embrace more experimental and creative uses of such MIDI composition than P.O.S and Mabbott dare attempt).

For a record so texturally ambitious, this seems to be a limitation more than an artistic choice. Perhaps, while the simplicity of Migos’ “Bad and Boujee” doesn’t warrant the breadth or charm of live instrumentation, Chill, dummy has a lot to lose by setting its sound world within these boundaries. And perhaps this audial threshold is an analogy for the record as a whole – well-intentioned and ambitious, but without the exertion necessary for such intention to coalesce.