An Echo of What Once Was

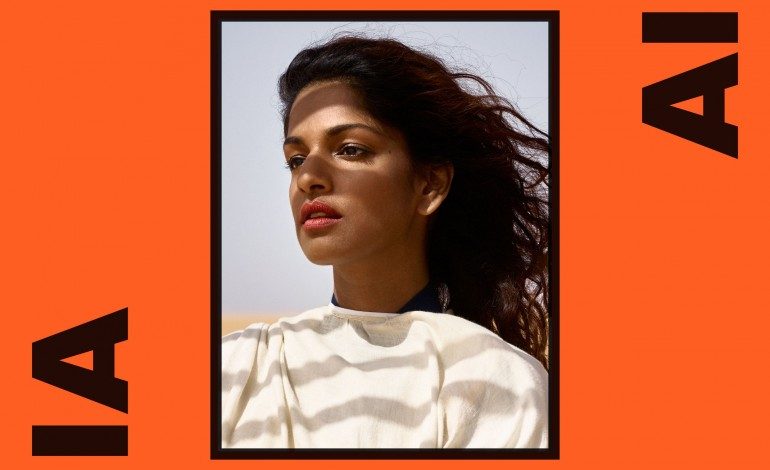

All hail the return of the public’s favorite Sri Lankan rapper and activist, M.I.A., who ushered forth the maelstrom of her new album, AIM, with a fanfare of single releases, retirement rumors and label disputes. Not known for conforming to the expectations of celebrity culture, M.I.A. certainly knows how to push buttons, constantly reeling in the public with her adept use of social media and her tirelessly vigilant stance on political reform. Eloquent and well-meaning as she may be, though, her latest work does not live up to the intrigue of her persona.

As always, M.I.A. delivers her music with an overt stance on the framework of current social issues; the beautifully-shot video for her single “Borders” is evidence of this. Unfortunately, though, AIM misses the mark in terms of its thematic unity, both musically and lyrically. Even through her collaboration with a bevy of the industry’s most cherished producers – including, but not limited to, Skrillex, Blaqstarr and Polow da Don – the cuts delivered feel generally uninspired, unable to rise above their benevolent message on the refugee crisis.

On 2007’s Kala, M.I.A. offered “Bird Flu.” On AIM, one instead hears “Bird Song,” which is a perfect representation of the detour the record takes from M.I.A.’s early work. Contrary to the unique samples, deftly street-smart lyrics and pure kineticism of the former, “Bird Song” wallows in minimalism, lilting along between a few sparse samples and a thumping bass line. The lyrics revolve exclusively around avian wit, highlighting phrases like, “I’m robin this joint” and “toucan fly together.”

At moments, M.I.A. reminds the listener of the vitality she presented in Kala and 2005’s Arular, with the cogent video for “Borders” and the intriguingly Eastern “Ali R U OK?” serving as extensions of the lineage one would expect. Too often, though, her new material is plagued by monotony and awkward rhymes. While M.I.A. was never associated with verbosity, this new record is uncomfortably rudimentary in its use of parallel rhyme, allowing forced repetition of vowel sounds to bludgeon the promise of a well-crafted lyric. This is particularly true of “Foreign Friend” and “Finally,” which feel like entries from a rhyming dictionary, as merely a few uninspired words are strewn in between each rhyme for a touch of context.

Perhaps the greatest disappointment in AIM is to see M.I.A. stumble upon what was once her greatest tool. The world-music samples employed in these songs are repetitive and frequently buried in the mix, washed out by pop synthesizers and drum machines. Additionally, when such Eastern sounds and rhythms are allowed to shine, they, too, often are regurgitations of previous ideas – note that the rhythmic foundations of “Go Off,” “A.M.P.” and “Visa” are essentially one and the same. By trying to adapt artistically to the mainstream, M.I.A. seems to lose sight of her own artistic merit, allowing her tediously auto-tuned cadences to fall on the front side of the beat as if to match wits with the trap-music generation, and foregoing percussive oddity for shimmering tonality.

In the song “Visa,” one hears a sample from M.I.A.’s own “Galang,” a track from her debut album (the aforementioned Arular). While an odd artistic decision, this route is ironically symbolic. In her new refrain, the listener hears an echo of the idiosyncrasy that used to define M.I.A.; however, an echo is all that it is, a reverberation lost in the sea of mundanity that is AIM.