The Last Episode

The past month or two, certain pockets of the Internet have been losing their minds over what’s been dubbed The Berenst4in Bears Problem. The supposition posits that the reason behind a number of people remembering the classic children’s franchise being spelled with an ein and not a ain is because our reality’s dimension has radically mutated or become enveloped by an alternate timeline (and not because, you know, human memory is unreliable at best). Last week, rapper and producer El-P took to Twitter to give his two cents: you know how i know we have deviated from our previous timeline? you want proof? DR DRE IS RELEASING AN ALBUM.

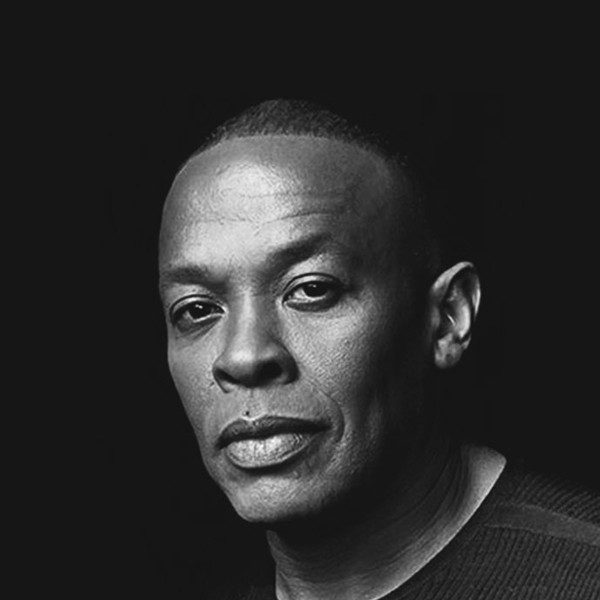

It’s true: after 16 years — and with less than a week’s notice — Dr. Dre has released (exclusively through iTunes) his follow-up to his heavily canonized 2001. Compton — not to be confused with the long-in-development, since abandoned Detox — arrives birthed from inspiration obtained while working on the feature film Straight Outta Compton. It’s a big record and high on melodrama; a knowing final statement from an artist and executive who, over his 30 year career, irreversibly bent the trajectory of American music. And while it’s a statement that so desperately wants to evoke importance and vitality, it too often gets lost in its own mythologizing. As Dre told Rolling Stone, its a statement meant to be “inspiring… motivational,” before explaining “the record is just me reflecting and I’m basically just talking to myself. It’s just me in the room and I’m talking to myself.”

For the most part, Dre’s reflections are largely impersonal and offer little insight into what makes the man tick. This makes sense — his lyrics have never been the product of a singular vision, but instead the work of a team (newcomers King Mez and Justus co-wrote almost all Dre’s verses on Compton). This arrangement has served him well in the past, whether he was talking about partying or uprising, but it isn’t so much suited for probing self-examination. As a result, when Dre isn’t discussing the history of his persona, he’s detailing the struggles that surround being a world-famous near-billionaire (“It’s All On Me”; “All In A Day’s Work”). Furthermore, age has not favored Dre’s voice, now smeared with gravel and rasp to the point of being borderline unrecognizable.

But Dre’s impact has always been derived from his work behind the scenes — credit not only to his production abilities but his hands-on involvement in developing and breaking artists from Eazy and Snoop to Eminem and Kendrick. In that tradition, Compton finds its peaks when Dre steps away from the mic and lets his music, direction and overall aesthetic be his presence.

Depending on the listener, Dre’s aesthetic can pose its own problems. Again, Compton is big. And melodramatic. Effectively, enjoyment of Compton will likely hinge on the listener’s level of appreciation for Dre’s more histrionic and quasi-operatic inclinations. At best, the beats swell and ebb with cinematic flourishes and progressive structures. At worst, veteran-emcee Cold 187um belts a sub-Andrew Lloyd Webber cry-rap about wanting to shoot himself before — apropos of nothing — pointing the gun at his wife and offing her instead (“Loose Cannons.”)

Which isn’t to say it’s all drama, and Compton is strongest when Dre breaks from linear storytelling altogether, goes hard, and shifts focus to issues outside his own legacy. “Genocide” blends Dre’s Chronic-era G-funk with contemporary tones and rhythms, complete with a barbershop-quartet-dubstep breakdown in the middle. “Deep Water” is a woozy beast, if somewhat confused in its messaging. The Snoop Dogg/Jon Conor tag-team of “One Shot, One Kill” places snarling blues riffs beneath two of Compton‘s best verses (another belongs to the Game, leading “Just Another Day,” and as to be expected, Kendrick steals the show on all three tracks he appears on). “For the Love of Money” is by far Compton‘s most infectious and accomplished track, even once the novelty of hearing Jill Scott atop a Dre production wears off. There’s also a gorgeous DJ Premier collaboration, with some moving sentiment from yet another new voice, Anderson .Paak (“Animals”).

But beyond these highlights, Compton fails to offer a consistent listening experience, falling short of its creator’s previous releases, as well as the work of his contemporaries. Too often, the record sounds like it’s trying to be a grand, important statement rather than being a grand, important statement. But the most remarkable thing about Dr. Dre’s swan song may not have to do with its music at all: apparently, all royalties earned from Compton will go toward funding a new community arts center located in the city of Compton, Calif. itself. This small act sets an excellent precedent, and one hopes others will follow suit. (Dre can clearly afford to do something like this, as can any other artists who orbit his economic status.) So while the impact of this final record may not be felt in the music itself, it will surely be felt in the background — the place where Dr. Dre has always been his strongest, and where acts of goodwill usually matter the most.