J. Cole Grapples with Environment, Love & Life

September 13, 1996: on this day, the world mourned.

While a consistently controversial figure in the eyes of the world, Tupac shook that world with a magnitude that far exceeded his age. And twenty years after the September shooting that took his life, Tupac’s influence continues to resonate, shaping the route, tone and dialect of hip-hop music and culture. However, though many artists routinely reference Tupac as a role model, few live up to this parallel in the affect of their output.

Cole is one of these few.

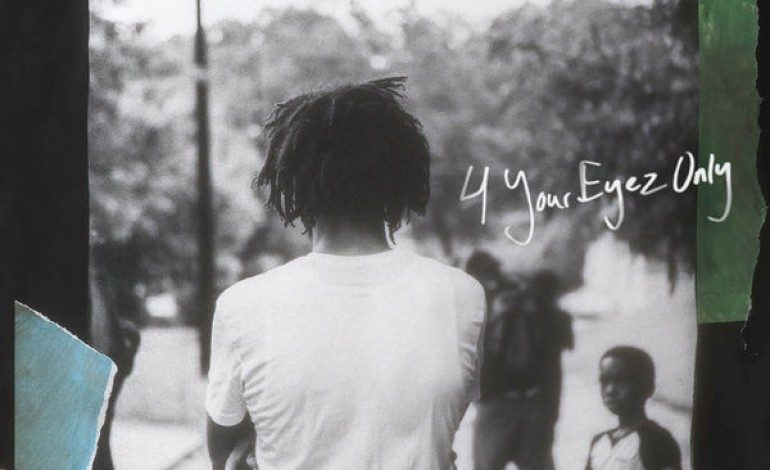

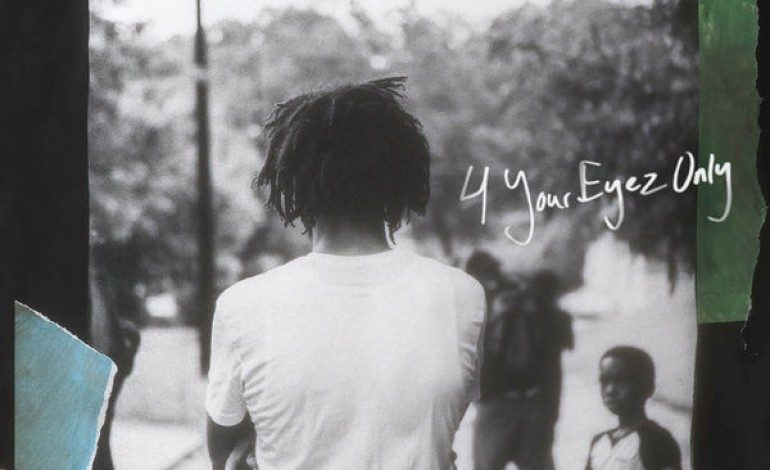

J. Cole’s latest anthemic release is titled 4 Your Eyez Only, a moniker that undoubtedly references Tupac’s 1996 All Eyez On Me. As ‘Pac did before him, J. Cole delves into the psychology and nuance of urban life throughout 4 Your Eyez Only; however, he allows himself to peer at this social setting through a host of lenses, painting his text and characters in a range of hues that accentuate not only their positives or negatives, but their humanity.

4 Your Eyez Only is not the first concept album conceived by Cole, who notably released 2014 Forest Hills Drive to widespread acclaim. However, while Forest Hills Drive was deeply internal – a thorough self-analysis of youth, growth and pursuit – 4 Your Eyez Only is the opposite, a venture into the life, love and demise of hustler “James McMillan.” As rumor has it, this character is based on one of Cole’s childhood friends, and while this narrative conceit occasionally grows tired or vague (particularly when Cole blurs the lines of perspective between himself and McMillan), the climax of the album and the implications buried within reveal a degree of shading and nuance previously untapped by the artist.

In a technical sense, Cole is firing on all cylinders for a great portion of the record. His rhythmic context is constantly keyed in, and his diction reflects the jazz lineage from which hip-hop emerged. Phraseology and articulation exist symbiotically, allowing for maximum effect in both lyrical capacity and rhythmic pattern and frame.

Additionally, in its devotion to jazz, the production of 4 Your Eyez Only mirrors the lyrics. Though perhaps less integrated or thematically annular than that of records like To Pimp A Butterfly or Black America Again, the jazz-informed production provides a lush surface upon which J. Cole orates. The effect of this acoustic instrumentality is most poignant when sonic universes collide – note the clipped vocal attack of the hook on “Neighbors,” shades of Tupac subtly juxtaposed with the legato hum of a reversed synthesizer and affected vocal samples. Such nuanced production and integration cannot be left uncredited, and the fact that Cole himself is behind the helm of this production makes this feat all the more stunning.

Within the world of film, the classic advice is the following: “Show, don’t tell.” J. Cole has become a master of this very idiom within the art of music. Though a few moments on the record fall flat (“Déjà Vu” lacks sophistication, and the first four minutes of “Foldin Clothes” could be summated in thirty seconds), the majority of the album is an exercise in vivacious imagery, communicating through scene and action rather than internal monologue. The album moves through these cinematic segments to conclude with its strongest track, which shares the title of the record itself (“4 Your Eyez Only”). While it has become easy to grow tired of the all-too-frequent eight-minute finale, “4 Your Eyez Only” commands the listener’s attention throughout. What Cole accomplishes is to turn the album on its head, to present an alternative angle from which the record ought to be viewed. And, as does all great art, 4 Your Eyez Only begs reanalysis in its final moments, drawing within itself in full knowledge of its forthcoming reexamination.

This being said, the strongest moment of the record – and one that is shaded in the subtleties of that very finale – is found within “Ville Mentality.” The listener hears the voice of a young girl that J. Cole met upon a visit to his hometown of Fayetteville, North Carolina. As she grapples with the love and loss interwoven in her tumultuous environment, one must consider the words that Cole raps at the end of “Foldin Clothes.”

“Niggas from the hood is the best actors,” he asserts. Actors, though, are still a step away from reality. The haunting echo of this child’s words in “Ville Mentality” are steeped in the harsh edges of nothing less than reality, and this knowledge holds more power than any yarn that an artist could spin.