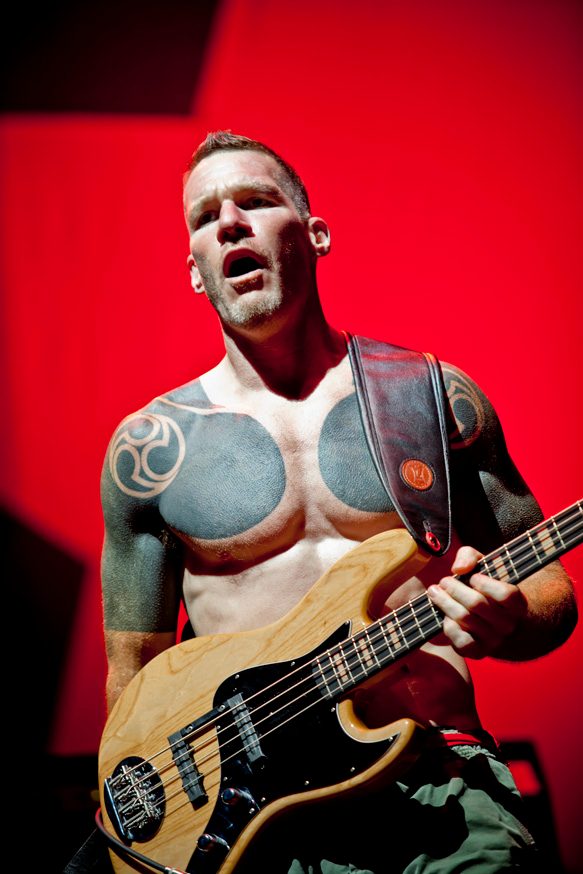

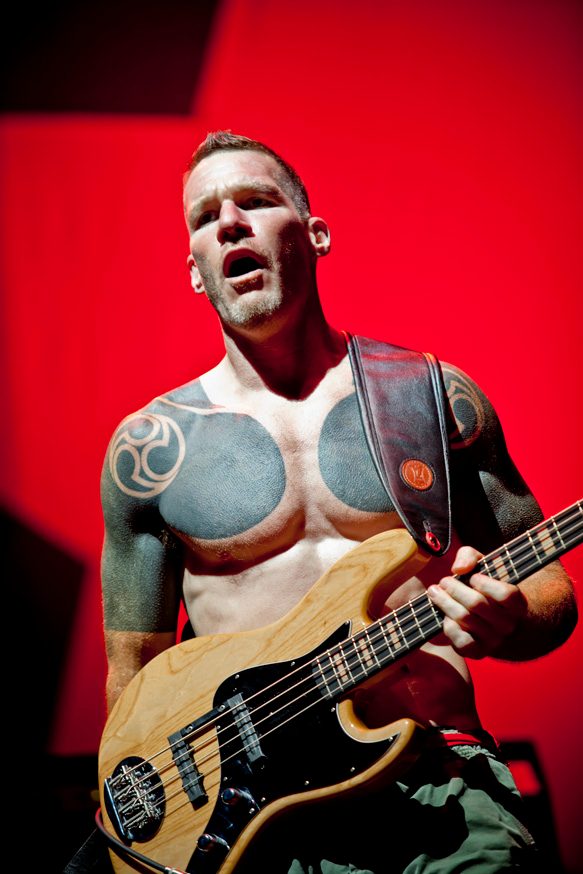

Photo Credit: Marv Watson

In 1991, Tim Commerford began playing bass in a musical project that featured two members of early ’90s metal band Lock Up—drummer Brad Wilk and guitarist Tom Morello—and his childhood friend Zack de la Rocha on vocals. A few years later, their output as Rage Against the Machine helped define the sound of a generation.

Though R.A.T.M. hasn’t played a show since 2011, Commerford, Wilk and Morello now perform in Prophets of Rage, which includes Public Enemy’s DJ Lord and Chuck D, and Cypress Hill’s B-Real. Their set-list includes a lot of Rage songs, but also cuts from Public Enemy and Cypress Hill’s respective catalogs, as well as a some covers, new mashups and original material. After a few shows in Los Angeles and New York, and an appearance in Cleveland coinciding with the Republican National Convention, Prophets of Rage embarked on a months-long tour titled “Make America Rage Again,” which continues through October 2016.

As well as playing in Prophets, Commerford is also fronting tour opener Wakrat, which features Laurent Grangeon on guitar and band namesake Mathias Wakrat on drums. Both bandmates are from France. We spoke to Commerford coinciding with the “Make America Great Again” tour’s stop at The Forum in Inglewood, California.

mxdwn: Rage Against The Machine was influenced by both punk and rap music. Now Wakrat is influenced, it seems like, by progressive rock and punk music. Would you say you’re drawn to bands that blur lines between genres?

Tim Commerford: I always tell people that I have no sort of preconceived notions about music, about what I like, or what I want to play. So much of it is being in the right place at the right time, and having listened to the right kind of music or whatever styles of music I was influenced by as a kid and a musician learning to play my instrument. I’m a fan of punk rock, no doubt, and I’m a fan of jazz music just as much. I really feel like Wakrat is a blend of punk, jazz and electronic—even though we’re guitar, bass, drums and vocals. It’s a blend of my influences, whatever they may be.

mxdwn: On the “Make America Rage Again” tour, you’re playing in Prophets of Rage, obviously, and opening in Wakrat at large venues. What’s it been like performing with a new band in front of larger audiences?

Tim Commerford: It’s interesting because obviously people are at the show to see the Prophets of Rage, so when we play, it’s exciting, electric, and people are ready to go crazy for the Prophets. That’s really great. Those are actually the easiest shows to play, whereas when we go on stage with Wakrat, a lot of times there’s not that many people in the house. Truth be told, the first few times we went on stage, it was a little uncomfortable for me. I’m not used to that. I’m very used to being in Rage Against the Machine, Audioslave and now the Prophets of Rage, where there’s a lot of rabid fans. We don’t have a record out with Wakrat. We only have a few songs on the internet. When we walk out on stage, a lot of these venues that we’re playing are amphitheaters, so there’s a lot of seats. People buy seats, especially up front. The seats that are up front, those people are the ones that went out the day they went on sale and bought the tickets, and they’re huge fans of the Prophets of Rage and they probably don’t know who Wakrat is. I really believe that there’s a lot of people there that don’t even realize that I’m in the Prophets of Rage.

It was a little uncomfortable, but that’s how you become a good band, by playing multiple shows in a row and playing all the time. So we became a better band. Somewhere along the way, we went from a band that was just playing our songs—we had thirty minutes, and were like, “okay, let’s try to get all nine of our songs that are on our record into the thirty minutes.” That meant trimming the fat, and trying to make the set go as smoothly as it could go. Then we turned a corner, and we went from a band playing our songs to a band that actually is putting on a show. I look forward to our show. I cannot tell you how therapeutic and psychological it is for me. It’s music, but it’s also performance art—so much of what I’m saying in between songs to tie the songs together, adjustments that we’ve made in our set, and new musical ideas that we’ve come up with since we started this tour that have been incorporated into our set. It’s therapy, and I dream about it. I wake up in the middle of the night, and I dream about things that I want to talk about and ways of tying those things into our set, and making it be something more than just a band playing their music.

mxdwn: In Wakrat, you’re handling lead vocals and bass, as opposed to just bass in Prophets of Rage. Do you think there are any challenges that are unique to being the voice of the band, as opposed to just playing bass?

Tim Commerford: For sure. It’s one thing to play an instrument, it’s another thing to vocalize something and play your instrument. Especially with Wakrat, where we don’t have any songs that are in 4/4 time the entire time. We have odd timing in every song, and that in itself makes it a challenge to play bass, much less sing on top of that. For me it’s breathing at the right time, and landing on the right finger. If that all comes together, things go smoothly. I’m blown away—I feel like it’s divine intervention. I can’t explain how it happens. Somehow I’m able to do it. I’m just holding on, and I just can’t believe that it’s happening. But I’m so proud of it. It’s really cool. I love it.

mxdwn: After the Brexit vote, Wakrat led a protest in London with signs referencing the track “Generation Fucked,” and other slogans like “Apathy in the U.K.” You guys declared Parliament Square to be the Republic of Wakrat. Do you plan on more political activity with Wakrat?

Tim Commerford: We do. We actually are just putting together our video for a song called “Sober Addiction.” Initially we made our video for “Knucklehead” in our rehearsal room, and I thought we should just do all our videos in the rehearsal room, use different ways of filming to make them look different, but do them all in the same place. I thought that was kind of punk. Then, somewhere along the way, I guess after we made the “Generation Fucked” video and we did the Parliament Square protest, I really felt like that had shades of “Sleep Now in the Fire,” the Michael Moore video we did with Rage Against the Machine. I’m really proud of that video, of “Generation Fucked,” because it really happened. It’s a real thing. I liked that, and I felt like we needed to make more videos that were like that. So we’re preparing our video for “Sober Addiction,” which I’m super excited about. I know it’s gonna be a statement and it’s gonna be political.

mxdwn: Was there ever a point before the Prophets of Rage tour where Rage Against the Machine was putting out new music?

Tim Commerford: I don’t know. We’re still a band. We just haven’t been doing much lately. As much as I’m a member of the band, I’m also a fan of the band. I’m always hopeful that there will be more music, that there will be more records, that there will be more tours. That’s where I’m at with it. I’m waiting patiently to proceed with Rage.

mxdwn: In both Rage Against the Machine and now Prophets of Rage, as well as Wakrat, you have this through line of political messages. Would you say the politics of the bands are comparable?

Tim Commerford: Truth be told, when we got together with Rage back in the ’90s, we never discussed what the political theme of the band was gonna be. The same goes for Prophets of Rage. It wasn’t a discussion. It’s just, you have like minded people that are coming together to make music. The message is there. With Wakrat, it’s the same kind of thing. There was no discussion of, “okay, we gotta make sure that we’re a political band, that we have something to say,” or anything like that. Some of the songs I don’t consider political. I think that it just comes from the heart. When your heart is aligned with the things that we dream about—in Rage, and in the Prophets and in Wakrat—we think about politics, we think about injustice and those things come out. That’s the way it is.

mxdwn: In Prophets of Rage you’re now working with two people who are legends in the rap world. Is playing with artists whose experience has primarily been in hip hop any different than in your past, more rock-oriented projects?

Tim Commerford: Well, Zack is a rapper. He’s an MC, a great one. I see Chuck and B-Real both working hard to be able to emulate him in the songs, and they speak openly about it. Zack is an amazing MC, an amazing rapper. That’s what he does within the context of Rage Against the Machine. I’ve been telling people, it feels with the Prophets very similar to the way it felt back in 1990 when we started writing the first Rage record, and we went, “Hey, let’s do hip hop vocals over rock music.” It felt almost too easy. It was so easy in that you’re not constrained by melody and chord progressions and the different things that you have to pay attention to when you have a melodic vocals over music. You can literally make noise and as long as it’s got rhythm, you can rap on it. For the most part, there’s a tempo constraint—maybe, but not necessarily. As long as you play within the parameters of the tempos of hip hop music, you can do whatever you want. And an MC can rap over it, and it sounds good.

In that light, we’ve been very lucky to be able to meld the two genres together like we have over the years. Here we are back now with the Prophets, and it feels very easy and it’s super fun. Whether we’re writing new songs, or playing old songs, or mashing up songs, or whatever. It’s almost like, you go “okay, let’s take the riff from ‘Freedom’ and let’s put ‘Fight the Power’ over the top of it and see how that sounds.” We just start doing it. When it’s done, it’s pretty cool. It’s fun, it’s exciting. I love hip hop music. I’ve always been inspired as much by the things that are being said. I love everything from KRS-One, to Public Enemy, to Cypress Hill, to the Geto Boys. I like older hip hop. I’ve been inspired by it and I’ve been politicized by it. It’s not just the lyrics, it’s also the music. It’s the basslines, it’s everything.